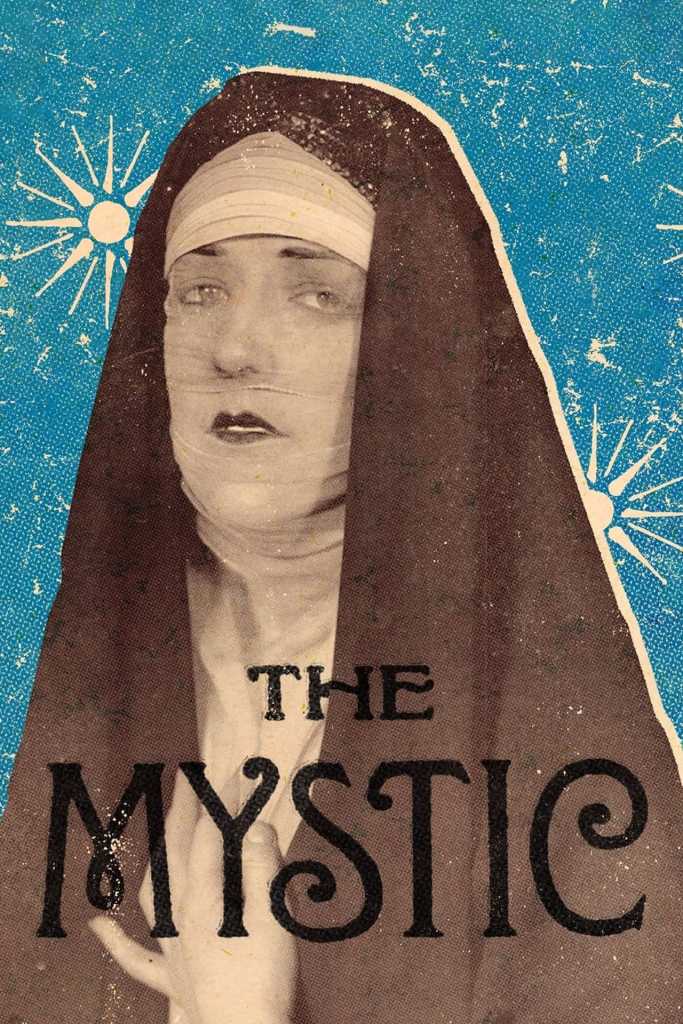

Today I’ve got a quartet of films that are approaching 100 years old, which is mind-boggling if you think about it. Starting with 3 films from early American film director Tod Browning, who was known for his horror films (called “the Edgar Allan Poe of cinema”), including 2 silent films and then a “talkie.” The Mystic (1925) isn’t really a horror picture, at least not by today’s standards, but does have a supernatural element to it. Zara and Zazarack are swindling little towns in Hungary with a fake psychic act when they are spotted by American Michael Nash. Nash thinks they can take their act to America and, with a bit more production value, increase their take. But once they are there, a determined police investigator and a lonely socialite may take down their act. Outstanding tension throughout the film, helped by a suspenseful soundtrack which often disappears during high-leverage scenes, this is a fun, intense drama. ★★★½

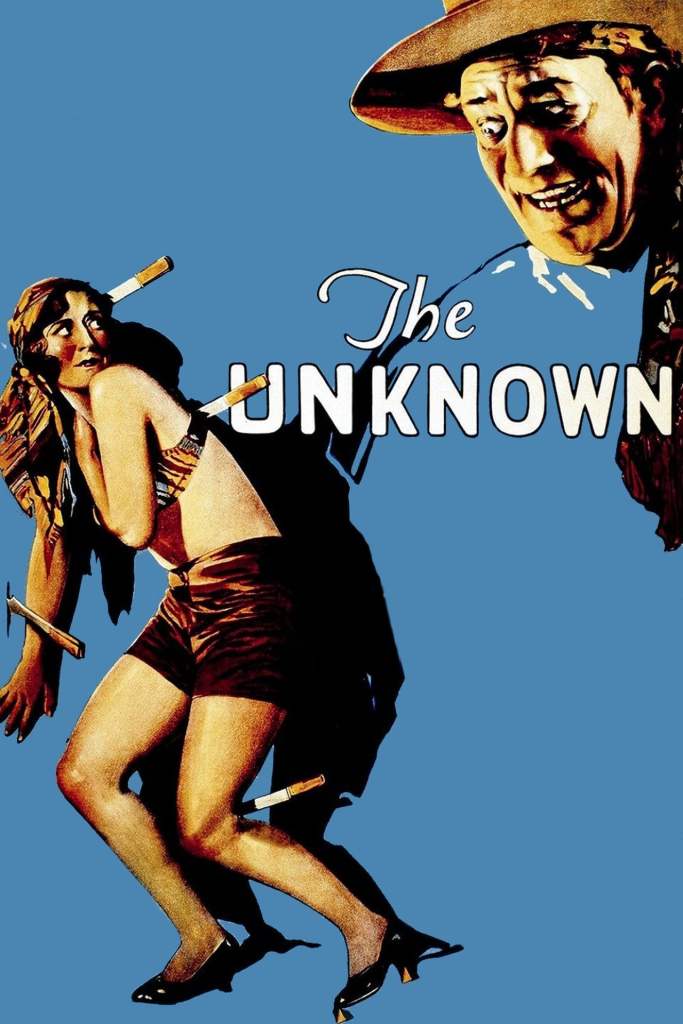

The Unknown (1927) features horror film superstar Lon Chaney (Sr) teamed with then-unknown Joan Crawford (I didn’t even know she got her start in the silent film era!). Chaney plays Alonzo the Armless, a circus freak who can toss daggers with his feet, to pinpoint accuracy. Like every man in the traveling carnival, Alonzo has eyes for Nanon (Crawford), the beauty in the show, but Nanon likes strongman Malabar. However, due to trauma from a man in her past, Nanon has a phobia for mens’ hands, and she shrinks from fear whenever Malabar tries to woo her. Nanon feels safe around the armless Alonzo, but he has a secret: he does have arms, but keeps them wrapped close to his body. If exposed, people would see that his left hand sports two thumbs, which would tie him to him to previous crimes, from which is on the run. In order to gain Nanon’s love forever, Alonzo makes the horrifying decision to have his arms removed, but will her fear of Malabar’s hands keep her Nanon from him forever? I had to laugh at some spots, like Alonzo using his feet to light a match and smoke a cigarette, or play the guitar, or twiddle his “thumbs,” but the ending is pure horror and completely absorbing. As Chaney showed in his horror classics The Phantom of the Opera and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, he was a master at arresting the viewer with his eyes; I could not turn away, he just grabs you and does not let go. ★★★★

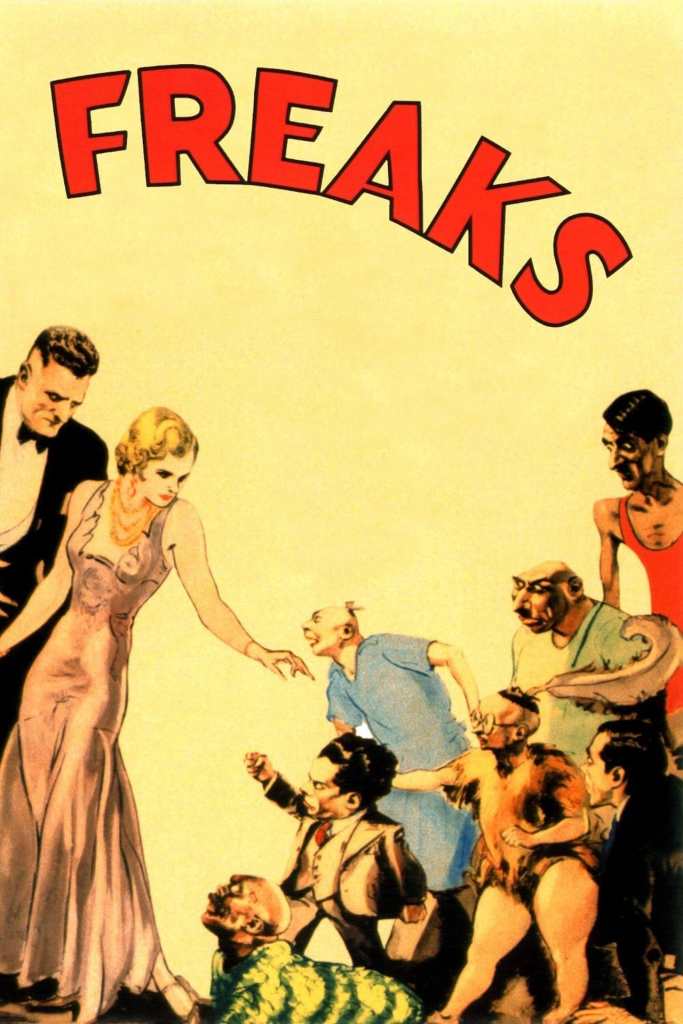

I’m not sure any one film ruined a career more thank Freaks did for Browning in 1932. It follows a traveling carnival and focuses on its sideshow performers. Hans, a little person, has eyes for trapeze artist Cleopatra, but she finds him and the other “freaks” revolting. That is, until she learns that Hans has a vast inheritance coming his way. She and carnival strongman Hercules hatch a plan to get Hans to marry her and then murder him for his money, but can she keep up the act when Hans and his fellow performers try to initiate her into their ranks? And when her scheme is unveiled, she must face the retribution from Hans’ friends, who will do anything for each other. This was a personal film for Browning, who ran away from home as a teenager to join a traveling circus, and had a soft spot for the society’s downtrodden. The sideshow performers in the movie were not “normies” under a bucket of makeup, they were real people with disabilities. There’s conjoined twins, little people, a bearded lady, a “half woman-half man,” armless people, “bird girls,” people with microcephaly, and more. During filming, MGM segregated the cast so that “people could get to eat in the commissary without throwing up.” Upon its release, the public cried that it was a gross and disgusting film, with moviegoers walking out from revulsion, or critics claiming it was exploitive. But I found it to be neither of those things, in fact, I think Browning treats his actors with compassion and understanding, trying to tell their story as human beings who stick together against tyranny. But in 1932, the damage was done, and Browning only made a handful of films again for the rest of his life. These days, the film is finally appreciated for what it is. ★★★★★

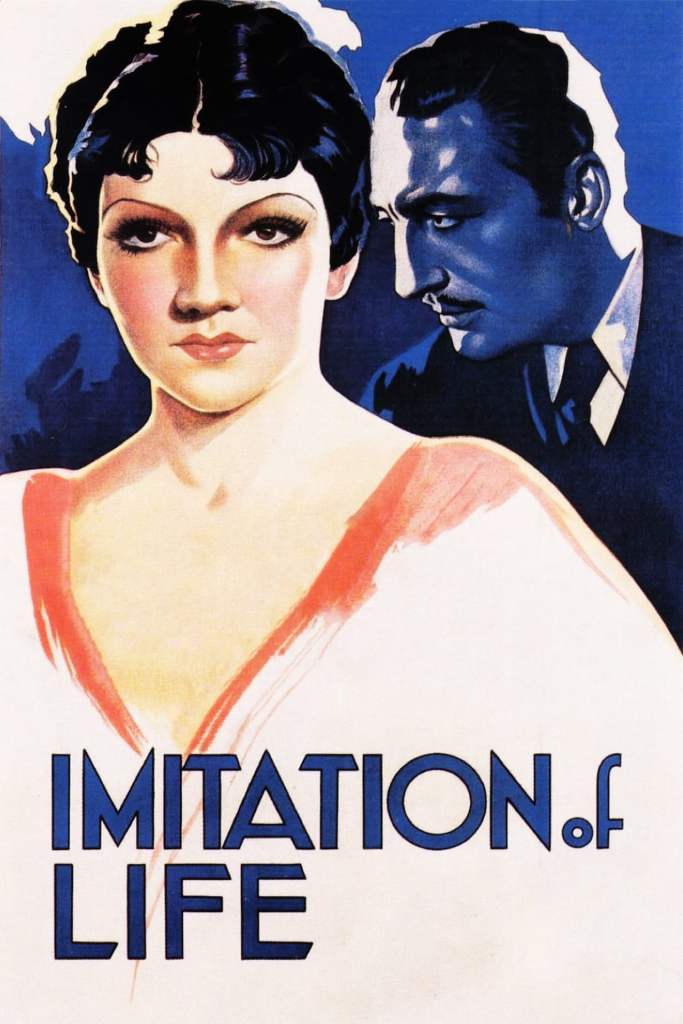

Imitation of Life is an entirely different kind of film, from director John M Stahl, and not just because, in 1934, it was now under the watchful eye of the Hays Code, so nothing too scandalous anymore. However, it does skirt the line, especially for the era it was made. Bea Pullman is a widow trying to pick up the pieces of her husband’s maple syrup business while raising her 2-year-old daughter on her own. A blessing comes in the body of Delilah Johnson, a black woman struggling to find a job where she can also watch after her young daughter Peola. Bea hires Delilah as a housekeeper, and with her help, sets out to build a life. Using Delilah’s secret pancake recipe, they open a flapjack restaurant where they can sell syrup by the bottle too, and it booms. Years later, they are living comfortably, and all seems well, except for Peola. Peola is very light skinned (in the original book the film was based on, her father was white; this was changed in the movie to satisfy Hays, and her dad was just a very light skinned black man too), and throughout her life, she’s tried to pass for white at school or in social situations, but her mom Delilah always seems to come in and ruin it for her. Now as a young woman, Peola doesn’t want to go to an all-black college, even a fine one that the now-wealthy family can afford. She ends up shunning her mother and heritage, but will only learn the error of her ways when it is too late. There’s also a subplot with Bea falling in love again, but then her daughter falls in love with the same man. There’s some great moments dealing with Peola’s passing, a stark look at racial divides that persisted from the 30s for decades after, but a lot of the rest of the movie seems like fluff. Maybe Stahl could have done more without the newly enacted Code breathing down his neck, but it felt very average on the whole. ★★½

- TV series recently watched: Nada (series), Mr Robot (season 3)

- Book currently reading: Dark Disciple by Christie Golden

One thought on “Quick takes on 4 early American films”