My second go-around with celebrated Japanese director Seijun Suzuki, and the first group was hit-or-miss with me. After this first movie, 1966’s Fighting Elegy, it’s still a miss. The movie follows a teenager named Kiroku who has all of the pent-up sexual tension that comes with being a teenager in an all-boys military school (sent there by his strict father for causing too much trouble). While at school, he’s living in a boardinghouse, and he’s set his eyes on his landlady’s daughter, the devoutly Catholic Michiko. Unable to get “his release,” Kiroku turns to fighting, taking combat lessons from a man named Turtle. The two young men go so far as to take control of a school gang, fighting their way to the top. Isn’t too long before their seats get hot, and they must flee to a new city, again running into the local gang. Michiko does make an appearance again before the end, but I had nearly forgotten her by then. The movie is outlandish to the point of silly, like when Turtle takes out a trio of school officials by flicking peas in their faces. The humor is over-the-top on purpose, but it was also over my head. I didn’t understand the mix of laughs and violence at all. ★

Branded to Kill, from 1967, is also over-the-top, but at least it has style, and an overarching plot that glues it all together. Hanada is an assassin, the “third ranked” killer in Japan, and he’s very good at his job. Against his better judgement, he takes a job from a woman to kill a foreigner on a busy street, but the job goes wrong when a butterfly throws off his aim, and Hanada kills an innocent bystander instead. This mistake will turn all of Japan’s underworld against him, but unfortunately for Hanada, that may have been the woman’s, or more accurately, her employer’s, intention from the beginning. Hanada holes up in an apartment, being hunted by the “number one” assassin, but maybe they become friends by the end? Better laughs in this film (including Hanada’s bizarre sexual fetish with the smell of steamed rice, or the femme fatale role, a woman with a death wish), and for me, much easier to follow than Elegy. Still, the movie pushed too many buttons with Suzuki’s bosses at the film studio, and they’d had enough. Suzuki was fired for making “movies that make no sense and no money” and didn’t make another film for 10 years. I think the execs were wrong on this one. ★★★

After a decade away from the spotlight, Suzuki returned in the late 70s. Zigeunerweisen was his second film after coming back, released in 1980. And it is a masterpiece. Gone are the jump cuts and goofiness that prevailed in his earlier films, and instead, Suzuki unfolds a longer, more mature surrealist drama. Aochi is a college professor happening through a small town when he comes across an old friend, Nakasago. Nakasago is in the midst of being charged with the murder of a girl found on a nearby beach, but Aoichi vouches for his buddy and Nakasago is let go (he later admits to Aoichi that he did kill the girl, but Aoichi refuses to believe him). Nakasago was once a teacher too, but has given up that life to be a nomad, never settling in one spot for long. What follows over the next two hours is a wonderfully bizarre head trip, leaving the viewer wondering what is real and what is dream, and even who is alive and who is a ghost. Nakasago and Aoichi share women, including each others’ wives, share experiences, share their views of life and death, and make a pact that will explode in the end. One of those movies that you can watch multiple times and still be left pealing back layers, trying to get to its core. ★★★★½

Kagero-Za ups the surrealism to level 10, and feels like one big dream sequence. A man named Matsuzaki meets a mysterious woman and is instantly drawn to her. Unfortunately for him, she may be dead (a ghost). He later learns her name is Ine, and she may be the deceased wife of Mr Tamawaki, who may have “other” wives to whom he won’t admit. Matsuzaki is drawn to one of these women, who looks an awfully lot like Ine. I use the word “may” a lot because honestly, you never know exactly what is going on in this film. The viewer is quickly lost in a maze without a map, but you get the feeling that there is a map, and it may (there’s that word again) unfold if you pay close enough attention. There are scenes scattered about where moments of clarity come together, and just when you think you have a handle on it, Suzuki turns it upside down again. Like Last Year at Marienbad, it is wonderfully confounding. Much ends up getting explained in the final act, when children put on a play which follows the paths of the 4 main characters, and the revelations threw me for a loop. ★★★★½

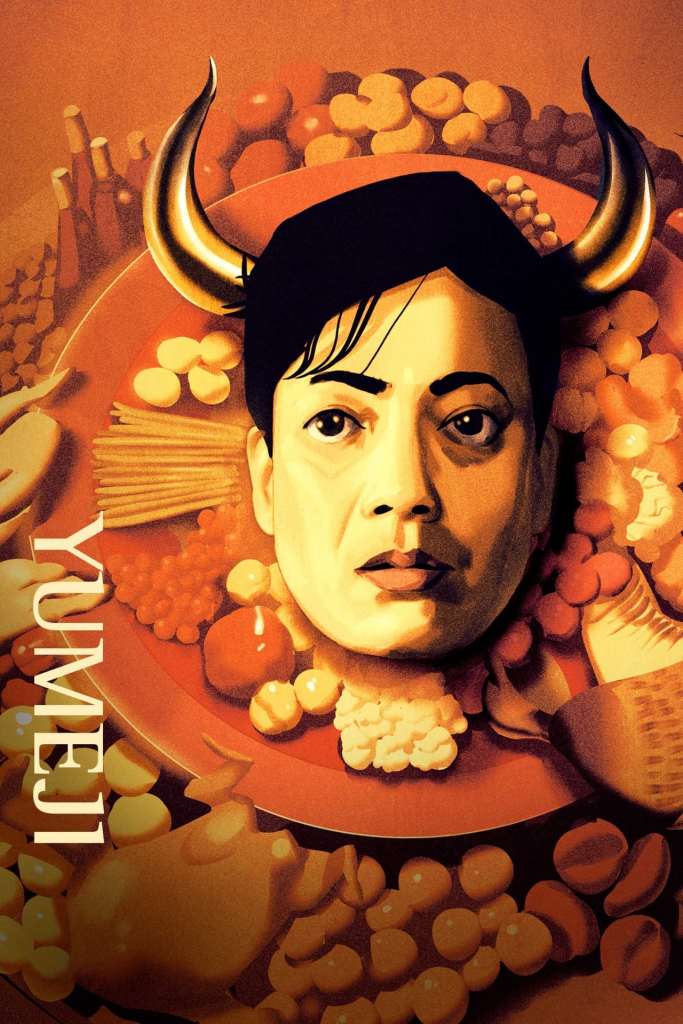

Suzuki’s run of hits ends with Yumeji, unfortunately, a fictional story about the painter Takehisa Yumeji. Yumeji is at a train station on the way to see his betrothed when he gets sidetracked in a little town, falling in love with a widow named Tomoyo. Tomoyo’s husband, Wakiya, recently drowned in the nearby lake, and she goes there looking for his unfound body, not for any sense of loss, but to make sure the jerk is dead. She and Yumeji hit it off right away, and things are looking fine for awhile, until Yumeji is out drinking one night and runs into a very-much-alive Wakiya. Wakiya is still on the run from a man who wants him dead (for dallying with his wife, as Wakiya is wont to do), even while he hints that he’ll kill any man who dallied with his wife Tomoyo while he was away. It’s a silly movie and incredibly slow. I swear Wakiya said he was going to go shoot Yumeji 10 times in the last 40 minutes, and, spoiler, it never happens. I think Suzuki’s late career successes with the above two films went to his head when making this one. ★½

- TV series recently watched: Fear the Walking Dead (season 8.1), Under the Banner of Heaven (miniseries), See (season 2), Jury Duty (series)

- Book currently reading: Dune House Harkonnen by Herbert & Anderson