Up today is a whole bunch of films from the silent era of American film. There’s a little bit of everything in here (except Chaplin, seen a whole lot of those already), starting with a trio of films by director Josef von Sternberg. Underworld set me off to a great start. A crime drama, it begins with a loudmouth gangster named “Bull” Weed as he’s pulling off his latest heist. Flush with money, he goes to the local bar to meet his girl, “Feathers” McCoy. There, Feathers is getting some attention from Bull’s rival gangster, “Buck” Mulligan, who also finds joy in belittling the town drunk, “Rolls Royce” Wensel. First off, let’s take a moment to enjoy all those names. Anyway, Bull comes to Rolls’ rescue and puts Buck in his place, but Buck swears revenge. Rolls and Bull become pals, and Bull is able to get Rolls sober, making him a confidant in his schemes. Clean and sober, Rolls is a different guy entirely, and Feathers appreciates his gentle touch, a much different man than the brash Bull Weed. Bull is the jealous type though, in fact, he later kills Buck at a party when Buck makes advances on Feathers. Now Feathers and Rolls have to decide if they should try to break Buck out of jail before he is hung for murder, or if they should take this chance to have a life together. This is simply a fantastic film. I don’t often look to silent films for stellar acting; there’s good stuff out there, but too often actors go overboard. Clive Brook in particular as Rolls is incredibly emotive and subtle, and George Bancroft as Bull is the perfect redeemable bad guy. One of those films that sweeps you up, and you forget that it is a silent picture. I was completely immersed. ★★★★½

The Docks of New York brings Bancroft back, this time as an antihero. He plays Bill Roberts, a steamboat stoker who has a reputation in every port as a lady’s man. Tattooed up and down his arms with crude pictures of naked girls, he works his tail off on ship, so he’s ready to party when they dock. He’s warned by the ship’s engineer, Andy, that he’ll only have the one night and is expected back the next morning. Heading to the local bar, Bill hears a splash, and rescues Mae from drowning. Mae, a prostitute, was attempting suicide, but Bill will have none of that. He steals some new clothes for her, nurses her back to health, and takes her down to the bar to party. In a drunkenly good mood, Bill exclaims that he’ll marry Mae to make her an honest woman. Mae can’t believe it (and neither can anyone else, including Bill’s boss Andy, who’s at the same bar; Andy likes to visit the ladies in port too, but this time he unexpectedly runs into his estranged wife, who has found comfort with other men in her husband’s absence). Bill hunts down a pastor and makes good on his promise that night, using Andy’s and his wife’s rings, since they obviously aren’t doing that couple any good. Of course, Bill has no intention of filing the marriage paperwork the next morning to make it legit, and deep down, Mae knows that too, but she’s happy with the one evening of bliss. But will Bill have a change of heart in the end? I think Bancroft made a better villain in the previous film; his surly character and sneering face don’t play as well for a hero, but the story is still wonderfully told. ★★★½

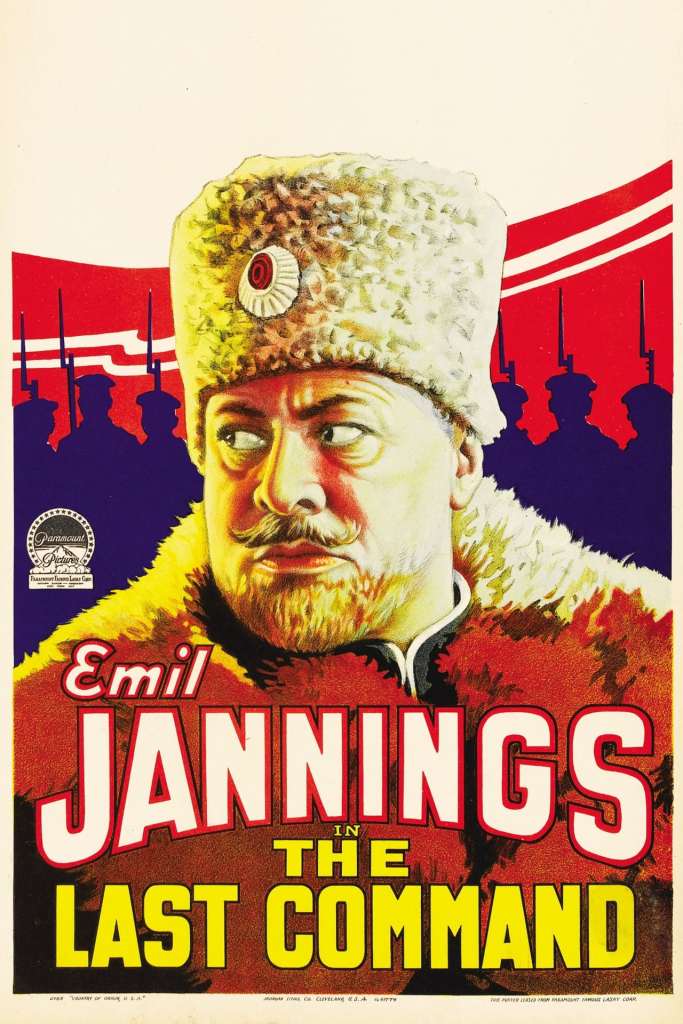

After The Last Command, I think I’ve found one of my new favorite directors. Von Sternberg’s last film today begins with Leo Andreyev, a Russian film director working in Hollywood in present day (1928). He’s reviewing photos of actors, looking for extras for his next film. He finds the picture of Sergius Alexander and sees something in him immediately. In Sergius’s bio, it says he was related to the former Czar and was a decorated general. Sergius is brought in for wardrobe and makeup, and the old man has a serious tick, and is obviously not all there in the head, making him the butt of jokes by the other actors. We then get a flashback 11 years ago, to 1917 Russian, during the Bolshevik revolution. Sergius leads the Russian army against a losing cause, but they don’t know it yet. Two spies are brought in to Sergius, a man and a woman, who are actors supposedly building morale for the troops, but who are really revolutionists. Sergius is instantly attracted to the beautiful Natalia, but astute viewers recognize her companion as the director in present day, Leo. Sergius beats Leo with a riding whip and sends him away, but makes Natalia his companion. She has a chance to kill him but sees that, while they are ideologically opposed, Sergius loves Russia as much as she, and she can’t bring herself to do it. She ends up falling in love with him, but their relationship obviously can never last. After Russia’s government falls and Sergius’s and Natalia’s love ends in tragedy, we go back to present day, and see that Leo had hired Sergius in order to exact a perverse revenge. But will he get what he wants (or want what he gets)? As Sergius, Emil Jannings won a Best Actor Oscar in the first Academy Awards ceremony in 1929 (there’s a neat trivia answer for you!). A tremendous film again, moving and heartbreaking, and I’ll need to look up more movies by this director in the future! ★★★★½

The 3 best silent film era comic actors were Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton. I’ve seen films from the first two (with more Lloyd coming up today), but The Cameraman is my first Keaton film. Known as maybe the best pure comic actor of the trio, Keaton did not disappoint. In the beginning of the film, Buster is selling tintype photos for a dime on the street when he sees and instantly falls for the beautiful Sally. He follows her to work, a secretary in the MGM news company. To be near her, Buster goes out and buys a (very cheap) video camera, in hopes of getting a job at MGM. Somewhere along the way, he does get a date with Sally. Everywhere Buster goes though, hilarity ensues. Whether it’s fighting with another man in the tiny changing room of a public pool (or losing his suit in the water), or getting stuck out in the rain after his date is driven home by another man, whatever the case may be, Buster is always the butt of the joke. At the same time, you have to appreciate his go-getter attitude, both in the role and as the actor. Keaton never met a stunt he wouldn’t do for a laugh, and took a ton of risks in his career. In one memorable scene in this movie, he climbs a long ladder up 20+ feet, and as he reaches the ledge at the top, the ladder falls away, leaving him dangling. He lifts himself up, only to see the ledge teeter and fall forward to the ground way down below carrying him (standing the whole time now) and landing on his feet. No nets, no mattress to catch him. Stunts like this pervade, and while a little scary to watch, I laughed and laughed, the whole way through. ★★★★

Keaton’s Spite Marriage unfortunately isn’t as strong. The story of a dry cleaner (Keaton) who falls in love with a stage actress (Trilby Drew, played by Dorothy Sebastian), it has the laughs but none of the emotional triumph that The Cameraman exhibited. Keaton is smitten by Trilby when he first lays eyes on her, and begins to attend her every performance, sitting in the front row and dressed to the nines. The cast and crew think he’s a millionaire, but Trilby isn’t interested; she only loves her costar Lionel. Lionel though has a wandering eye, and is now taken up with a young blonde. To get back at him, Trilby rashly marries Keaton one night, but immediately regrets it. Her agent tries to come to her rescue, begging Keaton to leave the city for a time so that Trilby can file divorce papers due to abandonment. Before Keaton can agree, fate pulls him off anyway. In a strange turn of events, he witnesses a crime, then hides from the criminals on a boat, which heads off to sea. Too bad for him that Trilby and Lionel are on the boat trying to reconcile. Keaton’s antics aren’t as hilarious in this go-around, though he still defies death (like when a mast swings out over the sea, with him dangling from the end). Instead of the laugh-out-loud guffaws of the previous film, this one elicited more chuckles. You do see the effects of sound film on this 1929 piece though. Though it has no spoken dialogue, the soundtrack is synced, and elements you see on screen are incorporated (the laughing and applause of the audience in the theater, the marching of solders on stage, etc.). ★★

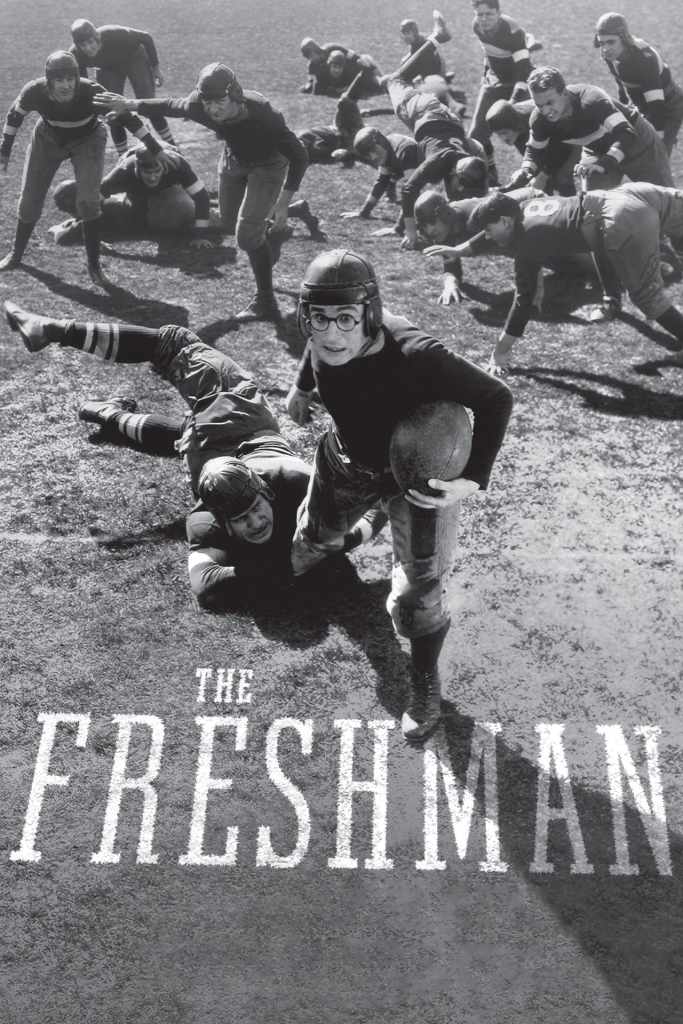

Harold Lloyd is sort of the forgotten member of the “big 3” of silent comic stars, though he was just as big of a draw at the time. I read a story somewhere that he didn’t allow his films on television, as he didn’t want them chopped up for commercial breaks and whatnot. Until home movies became a thing, this led to a generation-plus of viewers who regularly got to see Keaton and Chaplin, but never Lloyd, so his star diminished some. VHS/DVD/BLU and now streaming have reminded people of his genius. First up is his 1925 film The Freshman. Harold plays Harold Lamb, an incoming freshman to Tate University. He’s completely gung-ho, a little too excited, and wants to go in and immediately make an impression. Of course, others take advantage of that spunk, and it isn’t long before Harold is the butt of jokes on campus. It gets worse when he tries out for the football team, and ends up being the tackle dummy on practices, and the water boy during the games. The height of the laughs come when he throws a party at his boarding house, and wears a suit that unravels throughout the night. But in the final game of the season, Harold may get a chance to prove his mettle. Lloyd plays the lovable loser well, and his ability to keep a gag going is on view the entire film, but the film isn’t a real standout like some of the above films. ★★½

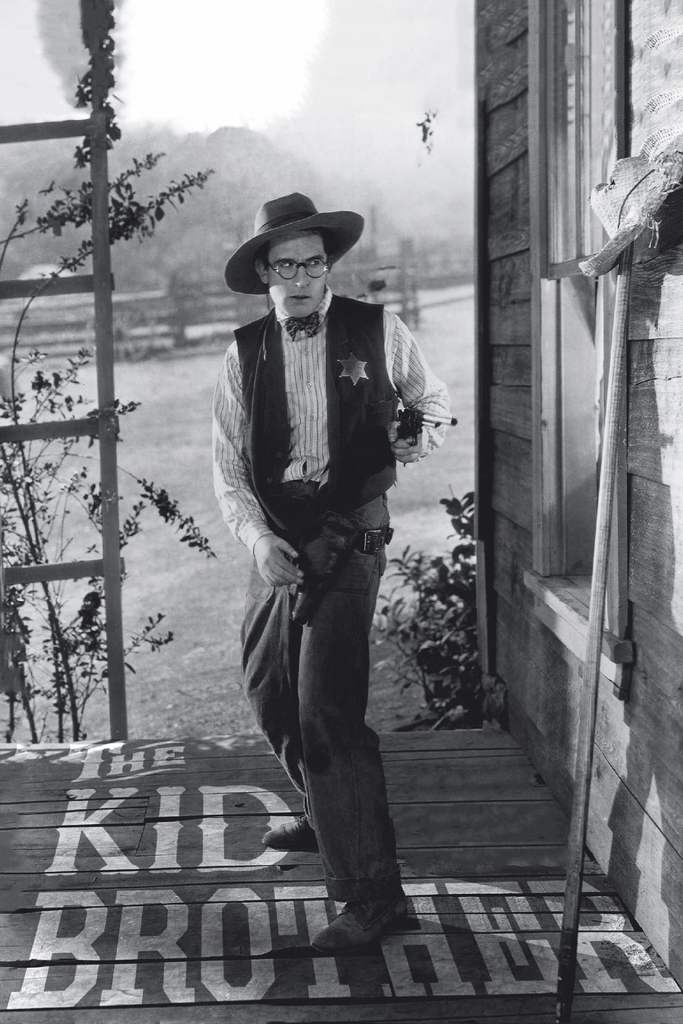

Lloyd is the underdog again in 1927’s The Kid Brother, this time playing Harold Hickory. As an early intertitle tells us, the stork probably laughed the whole time he was delivering Harold to the Hickory family; he does not fit in. His dad Jim is the sheriff of Hickoryville, and his two older brothers are just as big and burly as father Jim. Harold is the skinny kid and is always left at home when “men work” is to be done. However, when they are away one day, a traveling medicine show pulls into town, and go the Hickory home to get the sheriff’s OK to peddle their wares in town, and mistake Harold for the sheriff. Harold later tries to make it right, but of course things don’t go well. Like in The Freshman, there’s also a lady he’s trying to impress, but he doesn’t need to try as hard as he thinks he does, as he has her eye from the beginning. I had harder laughs than the above film; the comedic highlight is when the girl supposedly stays the night on the couch, and the brothers think she’s still there, feeding her food and coffee over and around a privacy blanket, when in reality she had left during the night and it is Harold on the couch. When they find they’ve been duped, the brothers go after Harold, but he hilariously evades them. When the town runs into serious trouble from a thief, Harold will need to step in to try to save the day. ★★★½

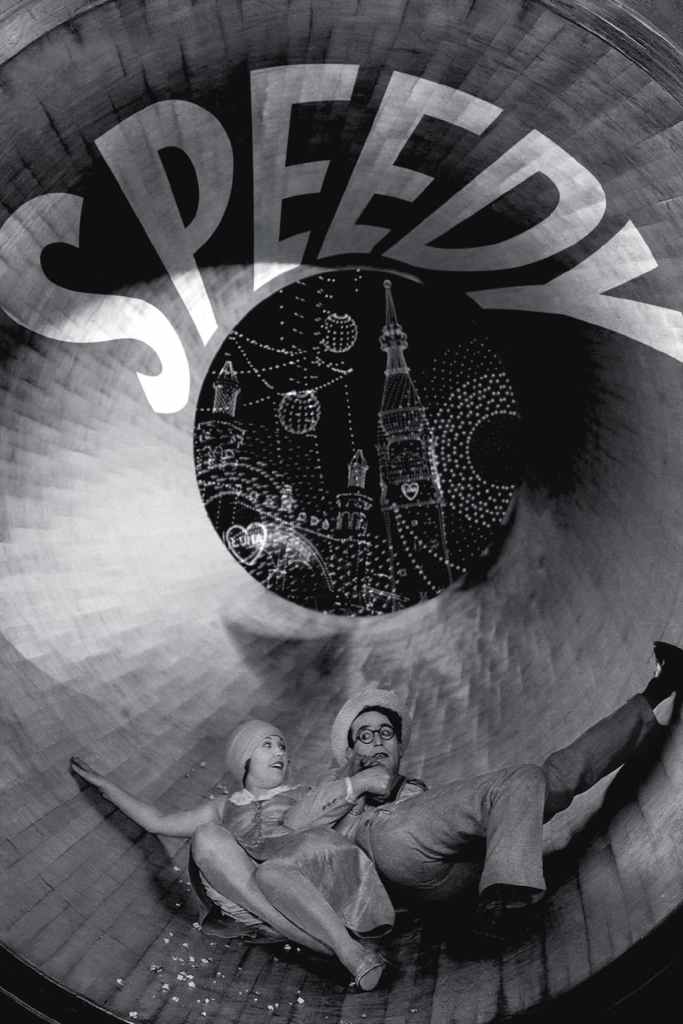

Speedy was Lloyd’s last silent film, released in 1928 (afterwards, he would be one of the rare silent actors to successfully transition to sound). It’s also my favorite of this trio of his films. He loses the underdog role, and is a popular man with a girlfriend from the beginning, though he can’t keep a job, and always lives on the edge of being broke. Especially after a funny day at Coney Island with his girl when everything wrong happens (though they have a good time). Harold’s one-day grandfather-in-law runs an old school horse-drawn streetcar, the last in New York, and he’s under pressure to sell it to a group who wants to modernize. But, at Harold’s urging, the man won’t let it go for peanuts. The group wanting to buy is ready to play hardball though, so Harold must once again save the day. The memorable gag in this film: Harold’s (again, only lasting a single day) job of taxi driver, where he gets a couple speeding tickets while driving cops after robbers (who disappear just long enough to not provide Harold his alibi), and a turn driving, of all people, Babe Ruth to Yankee Stadium. Buster Keaton may be more daring, and Charlie Chaplin may be more sentimental, but Harold Lloyd has them both beat on how to keep a joke going. In all three films, there were a couple times where he did a gag, ran it again, ran it again, and kept building on it, until you, as the viewer, went from minor chuckles to huge belly laughs by the end of it. ★★★★

- TV series currently watching: Star Trek Strange New Worlds (season 1)

- Book currently reading: Chapterhouse Dune by Frank Herbert

One thought on “Quick takes on EIGHT silent era films”