Yasujirō Ozu is a highly recognized director who, for my tastes, has had more average films than great ones. I’m beginning with one of his from the silent era, A Story of Floating Weeds. When most people hear “silent film” they think slapstick comedy, and there is a lot of that in this genre, since the visual gags can help carry the picture, but this particular film has a lot of heart too. It is about a traveling acting troupe who comes to a tiny town for a set of performances. The shows start off rocky and get worse when rains settle in, forcing low crowds and cancellations, but that is fine with the head of the group, Kihachi. He’s got other business in the town too: visiting his old mistress and seeing his son, who is now all grown up. The boy, Shinkichi, doesn’t know Kihachi is his father, only thinking him as a kind uncle who would visit every few years. Kihachi visiting his old flame makes his current mistress, a fellow actress, jealous, and she gets a younger member of the troupe to flirt with Shinkichi for some revenge. All plays out well in the end, though Kihachi does need to come clean for healing to begin. A fine film, and one that Ozu remade 25 years later, one that I’ll visit at some point in the future. ★★★½

Moving on to “talkies” with some Ozu films from the later 30s through the 50s. The Only Son was his first sound film, released in 1936. In a rural town, a young boy, Ryosuke, shows promise in grade school, but his single mother wasn’t planning on sending him on to middle school, as she just doesn’t have the money. His elementary teacher visits though, and persuades her to do so, as Ryosuke’s future will be a lot brighter with higher education. She vows to work hard so that Ryosuke can go to school in Tokyo. When we see them next, he is a grown man and his mother is coming to visit him in Tokyo for the first time. She’s struggled her whole life, but fulfilled her vow. When she gets to Tokyo, she finds that Ryosuke’s life has not been easy, despite his education. He got married, had a child, and is struggling to pay bills from his low-paying job as a night school teacher. For awhile, Ryosuke and his mom put on airs and try to pretend all is well, but it is obvious that she is disappointed in how his life is turning out, and he is ashamed that he didn’t amount to more. However, we soon learn that monetary success isn’t the only way to measure achievement. Beautiful film, and though it is Ozu’s first talkie, you can immediately see his mastery over both sound and silence, letting scenes breathe and not hurrying through the motions. Its pace may challenge some, but it isn’t a long movie and I loved it. ★★★★

There Was a Father has a very similar plot element to the above film, but this time it is a single father instead of a mother. Shuhei is a teacher raising a boy on his own, but quits teaching when a student accidentally drowns on his watch while on a school trip to a river. Shuhei becomes a laborer to pay for his son’s schooling, and as the years pass, the boy, Ryohei, goes to high school and then college, becoming a teacher himself. Like the above film, the two family members spend their entire lives apart; Shuhei works hard and never misses a day, only making the train trip to see his son here and there. Released in 1942, this sense of “doing your best for the greater good, even to the detriment of personal relationships” was applauded during Japan’s war times. Maybe because it was too similar in feel to The Only Son, which I’d just viewed, or perhaps it just wasn’t as good, but I wasn’t feeling it. ★★½

It’s very odd how some of these Ozu films just resonate with me. Such is the case with Late Spring, a quiet film (aren’t all Ozu movies?) about a single father, Shukichi, who raises a daughter, Noriko, to adulthood. She’s 27, and while their neighbors and friends all agree she should be married by now, Noriku has no desire to do so. She adores her father and wishes to stay in his household forever. With urging from an aunt (with a huge matchmaker syndrome), Shukichi devises a plan to get Noriku hitched: he tells her that he would like to remarry, but that he can’t do so with his daughter living under his roof. She takes the news hard, but wants to please her father and ultimately see him happy, so she agrees to find a man. Long, thoughtful takes, lovely scenes, and sharp dialogue all contribute to a joyful, moving experience. There’s also some sharp humor that often came out of nowhere, which was a pleasant surprise. Like I’ve said before, Ozu’s pacing may test some (and even me at times, despite my patience when it comes to movies), but this one’s a good one. ★★★★½

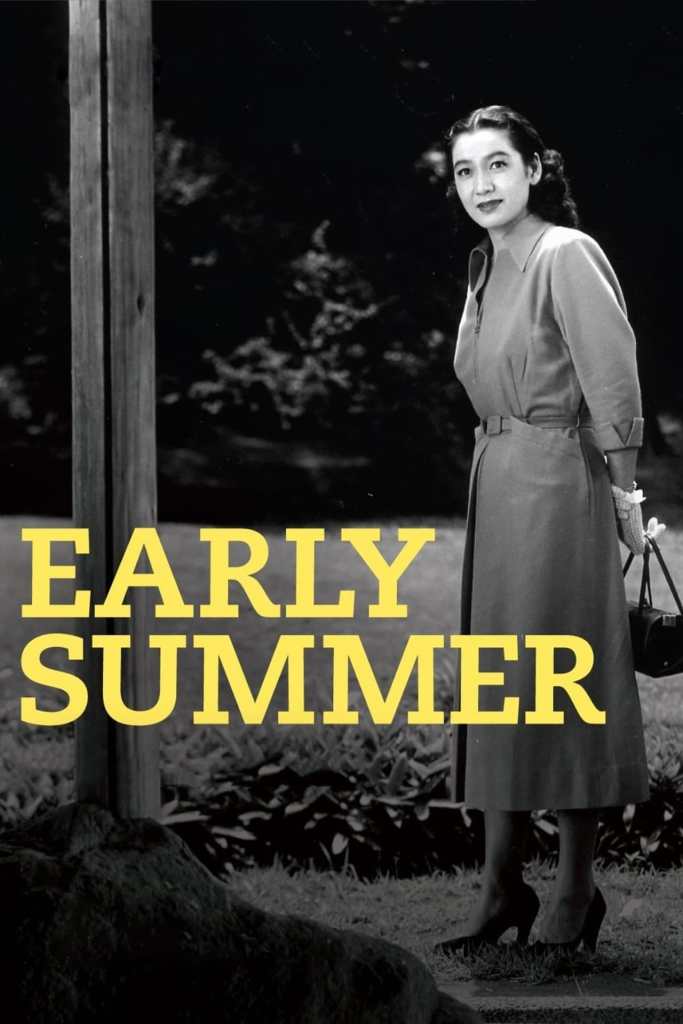

Much like two of the above films are similar, so too are Late Spring and Early Summer. This one also revolves around an unmarried daughter, with the same actress (Setsuko Hara) playing a character of the same name, Noriko. The 28-year-old Noriko has a loving family and an extended set of friends, some married and some single, and they all tease each other. Her parents though are done teasing: they want to see her married. They start to set her up with a single, never-married man, but they wonder if his age (40) will turn her off. Meanwhile, Noriko may find love in an old friendship, a person she never considered before. There are some truly great moments in this film; touching scenes that will move you as only the great films can. However, there are also some silly moments, attempts at brevity provided by various family members (but usually involving the two youngest boys), that come off as distracting and unneeded. I would have preferred to trim the fat and make a more direct family drama. It would have been more of a tear-jerker and a better piece on the whole. ★★★

- TV series currently watching: Top of the Lake (season 1)

- Book currently reading: Cloud Cuckoo Land by Anthony Doerr

Love this series (Quick takes)! Wonderful!

LikeLike