Shohei Imamura cut his teeth in the film industry as an assistant to Yasujiro Ozu, but when it came to making his own films, you couldn’t be more different. Whereas Ozu’s movies are quiet and contemplative, slow and serene, Imamura’s move at a frenetic pace. Coming up during the Japanese New Wave, Imamura wasn’t afraid to show true Japan, warts and all. Today’s first film is Pigs and Battleships, released in 1961. The film takes place in what was once a fishing village, but with a nearby port full of American soldiers looking for a little “something something,” a red light district has popped up to cater to those desires. Kinta is currently on the bottom rung of a gang but has dreams of working his way up the ranks. His girlfriend Haruko wants him to leave the gang and go straight. Each is facing an uphill battle in their lives. Haruko’s mother keeps pushing her to become a mistress to an American soldier, to bring money into the family, and Kinta’s superiors love making him the scapegoat, but never fulfill their promises of further riches. Kinta’s character comes off as a bit of bumbling, buffoonish idiot, and I had a hard time rooting for him, but I did keep hoping Haruko would find her way. She faces a ton of hardships, physical and mental, but her spirit stays strong. And there’s some dark humor/satire that is really brilliant, such as a scene where some Japanese folks are watching an American jet fighter air show, commenting on how their own self defense forces aren’t nearly as flashy. Didn’t they just get bombed by those planes 20 years prior? ★★★½

The brashness of Pigs and Battleships got Imamura sidelined by the studios for a couple years, but he returned even better with 1963’s The Insect Woman. Japanese cinema had historically been full of women who were submissive and passive, but not so with Tome. Born out of wedlock to a single mother from a poor farm family, Tome was going to do whatever it took to raise her family’s station, even if she wasn’t around to see the fruit of her labor. Throughout the film, which takes place over several decades, life hits her again and again. Whether she’s working as a maid or a prostitute, someone (and not always a man) always seems to get the better of her, but Tome is never broken. Her own daughter Nobuko, also born without a father, is left at the family farm so as to not expose her to what her mother has to do, but Tome always sends home what money she can. And in the end, just when it seems Nobuko may turn to her mother’s lifestyle when she too seems to be out of choices, you realize that all of Tome’s struggles over the years paid off. Fantastic film with tremendous acting from Sachiko Hidari as Tome. It’s not always an easy movie to watch, but it’s hard to find a better example of human perseverance. ★★★★

Unholy Desire (also known as Intentions of Murder) followed a year later. Again focusing on a woman in a bad plight, this movie follows housewife Sadako, who is treated more like a servant than a wife in her own household. Her husband Riichi berates her constantly and follows her finances like a hawk. Her mother-in-law is worse, constantly reminding Sadako of her poor background and sordid upbringing (her grandmother was a mistress who committed suicide, her mother was unmarried). While Riichi is having his own affair with a colleague, he hypocritically acusses Sadako of cheating on him. What he doesn’t know is Sadako has repeatedly been attacked and raped by Hiraoka. At first, Hiraoka just attacked Sadako while she was home alone one day, and his intent was only to rob. But afterwards, he developed a strange attraction and fascination with her, and has been stalking her ever since, attacking her whenever he found her alone. In a private moment, Hiraoka admits to Sadako that he has fallen in love with her, and wants her to leave her husband and run away with him. Having a man crave her has given Sadako a sense of power for the first time in her life, but can she translate that to her relationship with her husband? I think I like the intent of the movie more than the movie itself. It felt overly long, and the overarching plot elements of Sadako’s relationship with her husband and the brutality of Hiraoka are repeated so often that it started to get old. ★★½

While 1966’s The Pornographers has an attention-grabbing name, the film is a bit of a slog. It’s as straight-forward a comedy as Imamura can make, and while there are plenty of humorous moments, the movie is overly long and honestly boring at times, to the point that I started to have to take breaks to get through the final hour or so. It’s not that It’s bad, it’s just way too chaotic, with divergences in plot that will make your head spin. The main character is Subu Ogata, a man who will make a buck off anything to do with sex. He films low budget porn films, dabbles in prostitution, and sells snake oil sexual enhancement herbs to gullible men. Ogata lives with a barber named Haru; at first he was her tenet, but now he’s her lover, and this despite Haru swearing that the large carp in the nearby fish tank is her reincarnated dead husband, and he does not approve of her new relationship. Ogata also pays for Haru’s high-school children’s schooling. The boy, Koichi, has an unhealthy love for his mom, and the girl, Keiko, is growing into a woman’s body, and is learning how to use it to get what she wants. Much of the film, and its humor, revolves around Ogata’s various money-making schemes, and how everyone wants a piece of the pie, thinking he is raking in big money when he isn’t. The end of the film devolved into weird sexual advances and satire on what is and what isn’t taboo. Some highlights here and there, but not enough to warrant serious thought. ★½

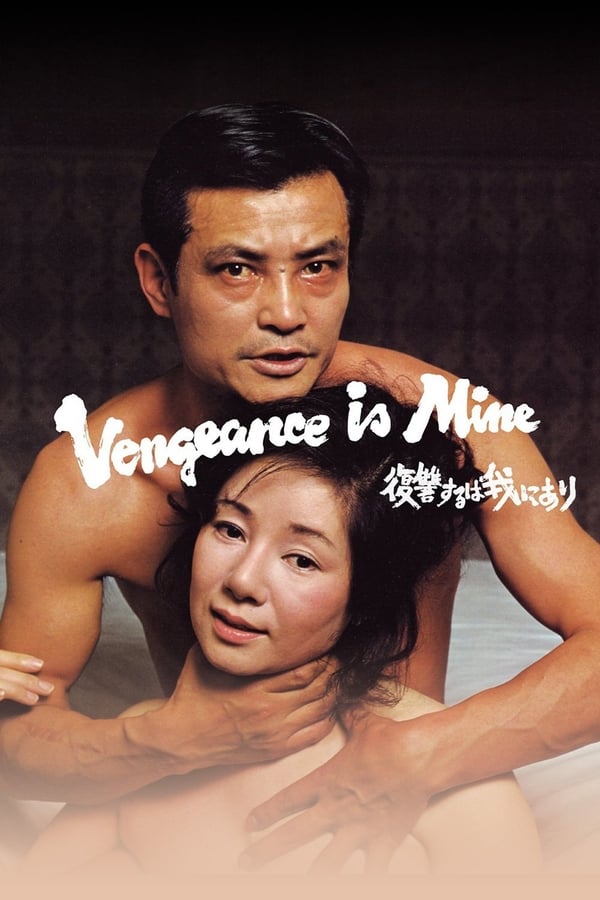

Jumping ahead a decade to the late 70s for Vengeance is Mine, which is based on the true story of a serial killer in Japan. The film begins at the end, with serial killer Iwao Enokizu arrested and questioned at the police station. It is next that we get the flashback, where Enokizu murders 2 men and takes their money. He afterwards goes on the run, staying one step ahead of the cops by defrauding unsuspecting people out of money in various schemes. But as the manhunt grows larger and the police paper Japan with wanted notices and even television commercials with Enokizu’s picture, he starts running out of places to go. There’s also a weird subplot involving his wife and his father, falling in love with each other. It ends up being somewhat important at the end of the movie, but mostly felt unnecessary, almost like Imamura just used it as a way to put his own personal stamp on the story. Like the previous movie, this one felt long (it wasn’t, it was 2 hours 20 min), and I would have liked to have seen it trimmed down somewhere for a more concise picture. ★★★

- TV series currently watching: The Flash (season 7)

- Book currently reading: Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky