For this group of films, I’m looking at movies from the Soviet Union. The Color of Pomegranates came out of the Soviet state of Armenia in 1969, directed by Sergei Parajanov. While this is a biographical film about the Armenian bard and poet Sayat-Nova, who lived in the 18th century, it’s not a movie with a story per se. Instead, it is a very lyrical art film. It takes moments of Sayat-Nova’s life and depicts them artistically, with very little dialogue, and only a few cue cards to tell the viewer where we are. It takes us from his childhood up to (through?) his death, with many scenes being nothing but shots of people doing repeated actions for a couple seconds in front of a still camera. Hard to make anything out of it, but I have to admit, it is a very emotional film. The color and scale of it wraps around the viewer, and while I often do not like experimental films, this one kept me enraptured. I really can’t put my finger on why either. The film was heavily edited by Soviet censors before release, who expected Parajanov to give them a more “standard” biographical movie. It was later restored by Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation, to get it as close as possible to the director’s original intent. ★★★

Dersu Uzala is a 1975 co-production of the Soviet Union and Japan, directed by celebrated Japanese director Akira Kurosawa (his only non-Japanese language film). Based on a memoir by Russian explorer Vladimir Arsenyev, the movie tells of the lasting friendship between Vladimir and Dersu, a nomadic hunter of the Goldi people (native to the Russian far east). In 1902, Vladimir is leading a small contingent of Russians in a survey expedition through the harsh taiga when they meet Dersu. Dersu is a hunter and a good one, and while his Russian is choppy and stilted, they are able to communicate well enough to hire him as their guide. Dersu’s knowledge of the land gets the group as a whole, and Vladimir in particular, through some rough spots, and Dersu saves Vladimir’s life on more than one occasion. When the expedition is done and Vladimir is ready to return home, he hopes Dersu will join him, but the city is no place for Dersu and he declines. Five years later, Vladimir is out in the wilderness again on a new exploration, constantly keeping his eye out for his friend. When they meet again, it is just like old times, and their bond is strengthened. As Dersu gets older though and starts to lose his edge, he has to face the facts that he cannot be the hunter that he once was. Shot on location in the Russian far east, the film encompasses the viewer in its harsh, barren reality, so while it has the look and feel of a grand epic movie, there’s still the tightness of a brotherly bond between our two characters. And it definitely has the feel of a Kurosawa picture. ★★★★

Come and See, from 1985 and directed by Elem Klimov, is regarded as one of the greatest films ever made. It is certainly an extremely powerful anti-war movie. It follows a young teenager named Flyora, and starts with him and a friend on a beach. You think they are just being boys and having fun, but it becomes apparent that they are digging up discarded weapons left behind by soldiers. We are in the midst of World War II, and Flyora is hoping that, if he finds a gun, it’ll be easier to join up with the partisan soldiers against the Germans. He does find a rifle, and soon after, leaves his family behind in their tiny village, and joins up with a contingent of fighters. He probably left for war the same way many young people did (and continue to do): hoping to fight for their friends and family, yes, but also seeking glory in battle. He finds that his views of war are not the reality. As the movie progresses, the atrocities of war get worse and worse, until a climactic ending where a neighboring village is massacred by Germans and their collaborators. Flyora and only a handful of others survive to witness the massive death and destruction. This movie hits you like a ton of bricks. As it moves from a frolicking young boy to a terror-stricken shell of a person, the viewer is hit with as many scars as Flyora. By the end, it doesn’t even look like the same actor. Over the course of the film, which can’t be more than a couple weeks, Flyora looks to have aged decades, until there’s nothing left. I felt as shaken as him. It’s a lasting, impactful movie. ★★★★½

Awhile back I watched Andrei Tarkovsky’s first five films, but that left his final two. Nostalghia was a co-production between the USSR and Italy, shot in the latter, and released in 1983. It’s about a Russian writer who travels to Italy while researching the life of a famous Russian composer. The composer had lived there for a time, and then after returning to Russia, committed suicide. Andrei has been following his footsteps, trying to get in his head, and his latest location is some ancient bath houses built around a mineral pool. After butting heads with Eugenia, his beautiful traveling companion and interpreter, Andrei becomes fascinated with a man named Domenico, whom the locals shrug off as crazy. Domenico has been trying for years to cross the mineral baths from end to end without letting his candle go out. He’s never succeeded. I know Tarkovsky. I know his movies can be challenging (frustratingly so at times). I have to admit I carefully watched this whole movie, and have absolutely no idea what it is really about. Hauntingly beautiful? Without a doubt. Accessible to most viewers? Not a chance. ★★

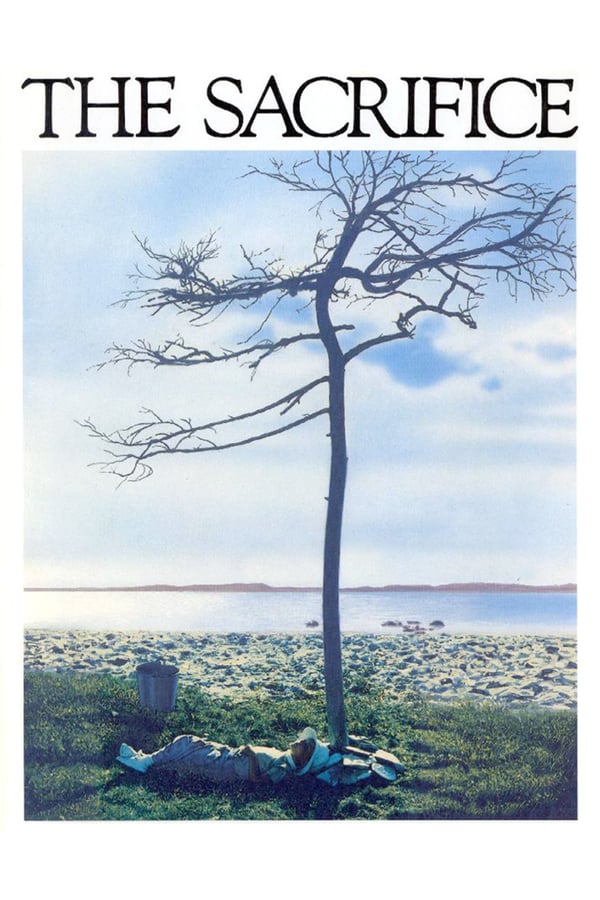

I’m cheating on the last film. It’s not a Soviet film, but it is from Tarkovsky, so, close enough? Released in 1986 after Tarkovsky had defected, The Sacrifice was filmed in Sweden. If you’re a filmmaker in Sweden in the 80s, lean on the best, and Tarkovsky did, casting Ingmar Bergman regular Erland Josephson (who also played Domenico in Nostalgia) in the lead, and hiring longtime Bergman cinematographer Sven Nykvist. The movie follows a family living in a large, beautiful house on a remote stretch of coast. Alexander dotes over his son, whom he calls his “Little Man,” but is indifferent to his wife and teenaged step-daughter. Alexander talks to his son in length on many topics, including Alexander’s lack of faith in God. One afternoon, with guests visiting, the house is rattled by jets flying overhead. They flick on the TV in time to hear that a catastrophic world war has broken out, and it is implied nukes have been launched and humanity is facing its end. Each person takes the news differently, from loss of hope, to shrugs, to nervous breakdowns. Once the initial reactions have cooled and Alexander is alone, he prays to God, awkwardly as it has obviously been a long time since he has, begging for something to save his family and everyone else. He promises that if God can save them, Alexander would be willing to give his family up, even his son, and leave everything behind. But if he magically is given that chance, and undo the tragedy, can he follow through? This film is magnificent. Deep and thought-provoking, with incredible camerawork from Nykvist’s steady hand. There are some super-long takes here: the opening sequence is like 9 minutes, and there’s a 6 minute take near the end. And they aren’t simple stay-in-one-place shots, they are moving, and characters are moving, and lots of things are going on on-screen. Incredible stuff technically, and a tremendous movie all around. ★★★★★

- TV series currently watching: Dickinson (season 1)

- Book currently reading: The Dark Tower by Stephen King

“Come And See”. Only seen it once. Not sure if I could make it through a second time. Just as haunting as “Night And Fog”. Devastating. Something everyone should experience. I think it’s power comes from – and this will seem odd, given some of its sequences – is its understatement. It doesn’t try to manipulate the viewer with suspense tricks or musical emotion button-pushing. Its haunting power comes from the matter-of-factness of how the events are depicted.

Harrowing.

LikeLiked by 1 person