Up today are a set of international films released by the Criterion Collection in Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, an important group that looks to preserve and restore films from around the world that are in danger of of being lost (as a side note, a lot of these restorations have been funded by the George Lucas Foundation, who spends beaucoup bucks restoring old films; he’s not just “the star wars guy”). First up is Sambizanga, from the country of Angola and released in 1972. Based on a true story, it documents the story of Domingos Xavier, an African man working in the capital city of Luanda under white Portuguese business owners, but who secretly meets people who are planning an uprising against their colonizers. When he is arrested, pulled from his house without explanation to him or his wife Maria, she sets out to find who took her husband and why. Maria was unaware of his political actions, and just wants her husband back. The police stations give her the run-around, always saying he’s not here, so go check that one over there. There’s good political commentary here, as Maria notices a loss of cultural self in the busy city centers, and points out men born in Angola who betray their neighbors for the white man’s money. Domingos’s friends and fellow organizers quickly realize why he was taken, and get the word out to be on the lookout for him. For a long time, we don’t know where he ended up either, until the final 30 minutes when we learn his fate. What happened to Domingos, and the outrage over it, was one event that led to the uprising he wanted, Angola’s war of independence, which they achieved in 1975. An important film about an important moment in the history of that country, but not exactly my cup of tea. The actress who played Maria is alright, but all of the actors are non-professionals (often not my favorite, as readers of my blog know) and though the story is good, the delivery of it left me wanting more. ★★½

Prisioneros de la tierra (known in the USA as Prisoners of the Earth or Prisoners of the Land) has similar themes but is more of a traditional narrative story. Released in 1939 and taking place in 1915, it is about the near-forced labor made by Spanish colonizers in Argentina in the early 20th century. Kohner is a foreman of a lumber operation, and he gets local laborers indebted to him in local bars through drinking and/or betting, and uses those debts to force them to work for him. These workers, called the mensú, or “paid monthly,” are darker skinned descendants of local populations and are looked down upon by Kohner and the other wealthy white people in the area. One mensú is Podeley, who will not be cowed by Kohner and his ilk. Unfortunately for him, he and Kohner both have eyes for the lovely Andrea, the daughter of a doctor brought in by Kohner to treat illnesses in the workers (not for any love of them, just to keep them on the line working). Unbeknownst to Kohner, Andrea’s mother was half mensú, and she doesn’t see the class difference that others do. There doesn’t seem to be much that sets this film apart from a plethora of others like it, until the end of the film. It has an explosive and violent final act, the likes of which you didn’t see in Hollywood films in the 30s. It completely flips the script, and I did not see it coming (though maybe I should have if I’d been playing closer attention). ★★★½

Now we’re talking. Chess of the Wind (and the story behind how it was almost lost for good) is the kind of film the WCP exists to save. From Iranian director Mohammad Reza Aslani, the film follows a household in the aftermath of the death of its wealthy matriarch. Two people seem to have equal claim to the money left behind: her daughter Aghdas, and her husband (Aghdas’s step-father) Hadji Amoo. The two have obviously never liked each other, and while Hadji Amoo seems to have the best legal standing to get the money and estate, Aghdas will not go down without a fight. Other key players are Hadji Amoo’s adult nephews Ramezan and Shaban, hangers-on who also have eyes for a payday. Ramezan is engaged to Aghdas, but it is apparent to all (and maybe even to Aghdas) that he just wants money, and Shaban has cozied up to Aghdas’s young maid Kanizak. Greed will make people do terrible things, and everyone in this film is only seeing dollar signs. Aghdas conspires with Ramezan to kill Hadji Amoo, and they stuff his body in a large tub in the cellar, but afterwards, people around town remark how they’ve seen him here and there. When Aghdas and Kanizak go down in the cellar, they can’t find the body. Is he not dead, or is he a ghost? Great suspense and the sound and dark interiors of the house (where nearly the entirety of the film takes place) add to the tense feeling permeating through the film. This movie was shown just once in Iran before the 1979 revolution, after which it was banned (for many reasons) by the new government, and thought lost. The director’s son found the original negatives in a junk shop in 2014, saving this tremendous film. ★★★★½

I couldn’t connect with Muna Moto, a mid-70s film from Cameroon. Shot in black and white and with an almost documentary-like feel, it begins in the end. Ngando is at the wedding celebration of a woman named Ndomé. At the party, he grabs her young daughter and runs, being pursued by her and the other villagers at the party. We then get a flashback, and learn that Ngando is a poor man but he works hard, and hopes to save enough money to use as a dowry to marry his girlfriend Ndomé. The two are very much in love, but her family is insistent on a traditional dowry, and Ngando doesn’t have it. He goes to his wealthy uncle Mbongo, but when the uncle sees Ndomé, he gets an idea of his own. Mbongo already has 4 wives, three of his own choosing as well as Ngando’s mother, who married Mbongo after her husband’s death, as is custom in the area. None of the 4 have given Mbongo a child, so when he sees the young Ndomé, he thinks this is his chance to finally procreate. He supplies the dowry, and the wedding date is set. Ndomé will not go as the virgin he wants though, and begs Ngando to give her a child, so they can share a child even if they will not be married. Thus setting up the ending/beginning of the film. Obviously a critique of traditional customs against a changing society, the film is done well but I just wasn’t engaged in it. It slows down to show local dances and/or events going on, which adds to the documentary feel, but which have nothing to do with the movie, and while interesting, I’m not usually a doc kind of person. ★★

Two Girls on the Street is a Hungarian film from the late 30s, following two women each overcoming personal disaster. Again dealing with issues that Hollywood Code prevented, the film begins with Gyöngyi, who is pregnant from her wealthy boyfriend but suddenly discarded as he chooses to marry someone else. She loses the child, and to try to leave her shame behind, moves to Budapest and finds work in a band (she plays the violin). Walking the streets one night, she comes across Vica, a very young woman who happens to be from the same hometown. Vica doesn’t have the education and “proper upbringing” that Gyöngyi has, and is working as a bricklayer, but facing constant harassment from the predominately male workers. Vica is attracted to the lead architect of build site, but the young and naive Vica panics when he makes a move on her. Gyöngyi finds her distraught, and takes her home to her place. Together, the two women work to improve their situation, first writing home to Gyöngyi’s father to ask for money (he agrees, missing his daughter after all this time) and then moving to a better part of town. Gyöngyi enlists a friend to educate Vica, and starts to see the younger woman as the daughter she never had. Gyöngyi sees a future for Vica, if they can evade the past that haunts them, but unfortunately they stumble upon the architect. He doesn’t recognize them, and he and Vica start dating, much to Gyöngyi’s chagrin. The movie has a great story for much of its length, but bogs down in the end. It makes these great, ahead-of-its-time criticisms of sexism and the wealthy elite, and then takes everything back in the end when Vica just falls in love with him and gets herself elevated to his status. Decent, but could have been great. ★★★

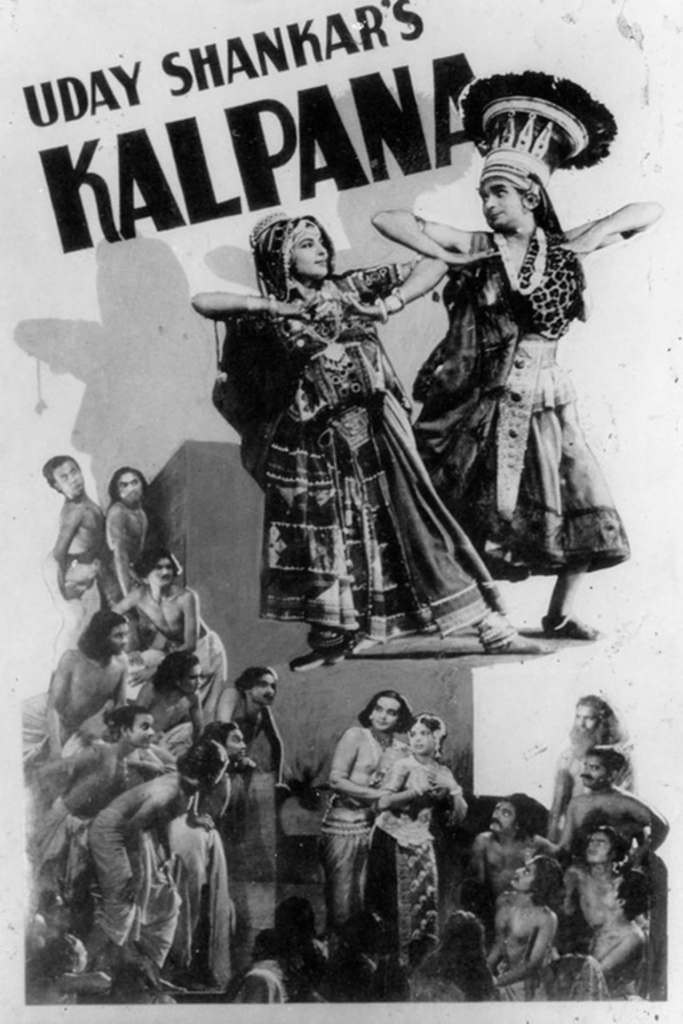

The final film today, Kalpana, is an interesting movie from Indian dancer Uday Shankar, older brother to famed sitarist Ravi Shankar. Uday plays a version of himself, Udayan, who is striving to promote pride in the actions and people of India. To that end, he is wanting to open a cultural center that will teach dance, among other schools of thought, because he thinks that universities have strayed too far from India’s heritage roots, and students are only learning “book knowledge” with no learning of the history of their own people. While Udayan is gaining financial support along the way (while also telling off some high-and-mighty people who have become “too westernized”), there is a love triangle story going on as well. While off learning his craft, Udayan meets a woman named Kamini and the two start a relationship, but he later meets a dancer named Uma, a woman Udayan has had visions of in his dreams. Kamini is immediately jealous of Uma’s and Udayan’s instant connection, and fate seems to be on their side no matter what Kamini does. The story is told with many fantasy, dream-like moments, and pulls heavily from India’s lore. There’s lots of dance numbers, as you’d expect, either furthering the story with a tale to enhance what is going on, or as an interlude. Everything is very entertaining, so much so that I’ll forgive the over-acting from these non-professional actors. The exotic feel of the Indian dance helps a lot, and it feels like you are sharing Udayan’s dream. ★★★½