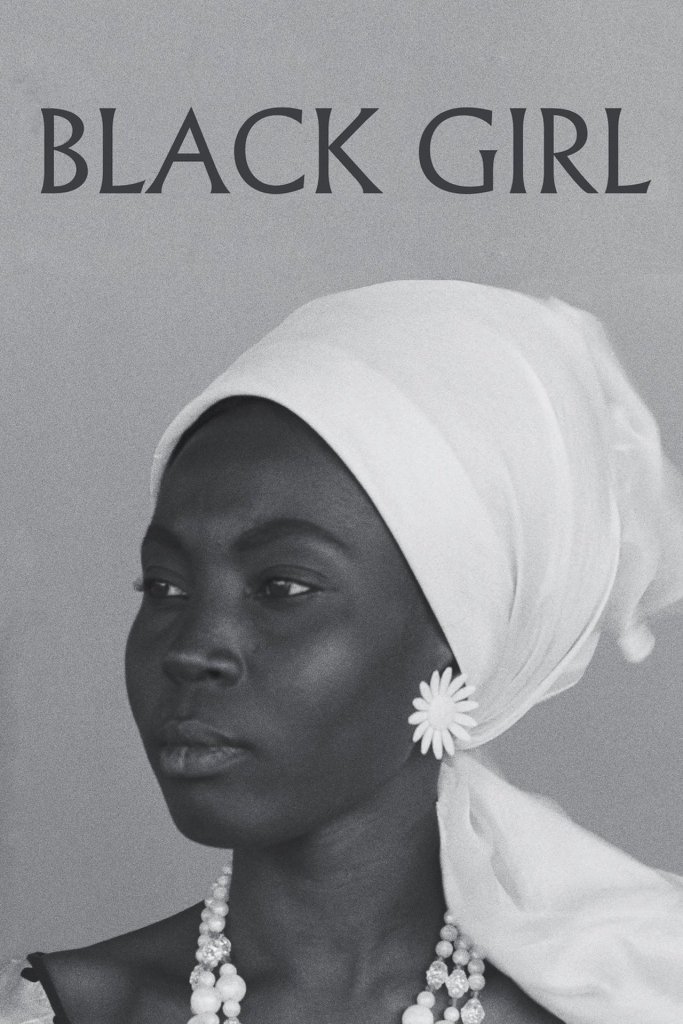

Today I’ve got a series of films from “the father of African film,” Ousmane Sembène. A prolific author and film writer/director, he told stories from the perspectives of his native land and people in the 50s and 60s, long before much thought was given to such. Up first is his first feature film, 1966’s Black Girl. A biting narrative on the lingering colonial attitudes in a post-colonial world, the film follows a young woman named Diouana as she is hired by a white couple to be a nanny to their children. In the beginning of the film, Diouana is struggling to find work in Senegal, but fortune seems to strike when she gets the above mentioned job. The family brings her to France, where Diouana hopes to see the world and to make money to send home. However, the work is not what she expected. The children aren’t even around, currently off at boarding school, and Diouana is instead the family maid, cooking and cleaning. Weeks go by and she isn’t even allowed to leave the house; the only parts of France she can see is from her bedroom window. The family’s matriarch quips, “Who would she go see? She knows no one here.” It’s easy to hate this woman, she’s demanding and condescending, and frankly a real bitch, but her husband is just as bad in his own way. Though seemingly kind to Diouana, his apathy and his failure to grasp why Diouana is unhappy is appalling. The couple thinks they are “giving Diouana a better life” but being a prisoner in a home, barely a notch above slavery, isn’t any life at all. The fate awaiting Diouana is really her only choice. Very stark film. ★★★½

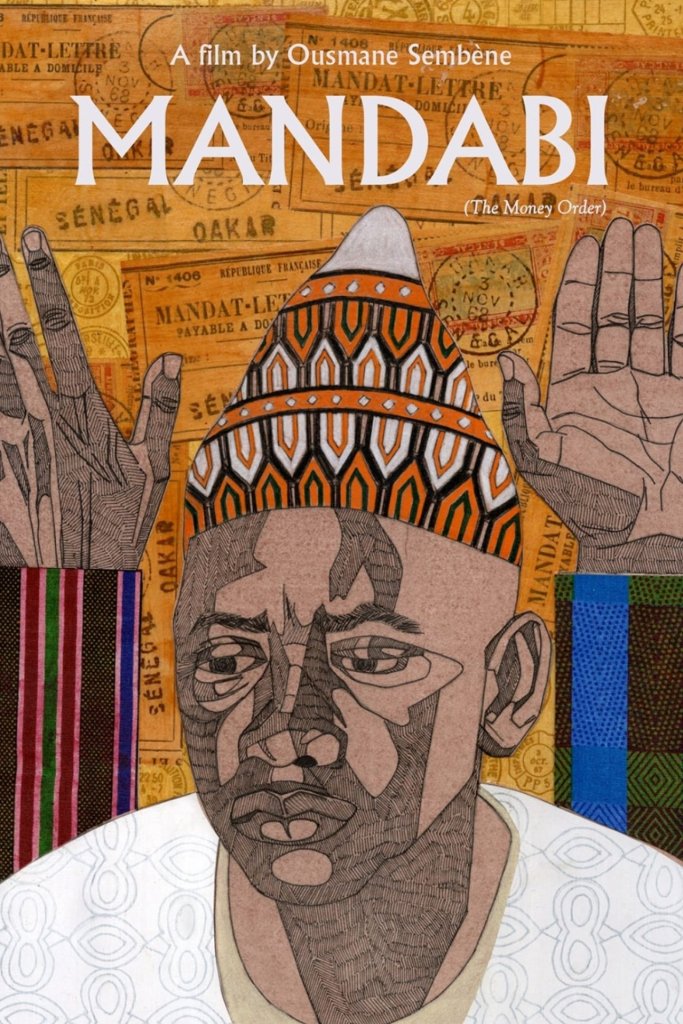

Two years later, 1968’s Mandabi shows one earnest man’s struggles in a city where corruption has bloomed in every other man’s heart. In Senegal, fervent religious Muslim Ibrahima is poor, having been unemployed for 4 years, but he refuses to let his two wives beg or borrow to help support their 7 children. He goes out every day to scrounge what he can, but usually returns home empty handed. Once again, fortune comes when he receives a letter from a nephew working in Paris, attached with a money order for 25 thousand francs. Illiterate, Ibrahima is unable to read the letter, but he immediately praises his good fortune and goes to the local store to get rice for the family (on credit this time). The next day, Ibrahima tries to go to the post office to cash the money order, only to be turned away because he lacks a proper ID to prove identity. A man at the post office offers to read the letter for 50 francs, which Ibrahima reluctantly agrees to (on credit), and in it, the nephew asks Ibrahima to give 20 thousand to his mom (Ibrahima’s sister), 3 thousand to another, and to keep 2 thousand for himself. Unfortunately Ibrahima is already over that 2000 thousand in promises for his recent purchases, but that’s a worry for another day. He is directed to the police station to get an ID, but they refuse without a birth certificate and photo. He goes to the City Office for a birth certificate, but they refuse because he doesn’t know what month he was born in. He approaches a wealthy nephew in the city, who promises to help get the items he needs (for a fee), but Ibrahima is swindled out of another 300 francs when he tries to get a photo taken. All along his trips around town, Ibrahima is constantly approached by beggars and friends (who have heard about his good fortune), all with their hands out, and being the good man that he is, Ibrahima can never say no, until his crippling debts start hanging over him, even as the promise of wealth seems further and further away. If you needed a poor vision of what humanity has become, look no further. Also has the distinction of being the first film made in an African language (Wolof). ★★★½

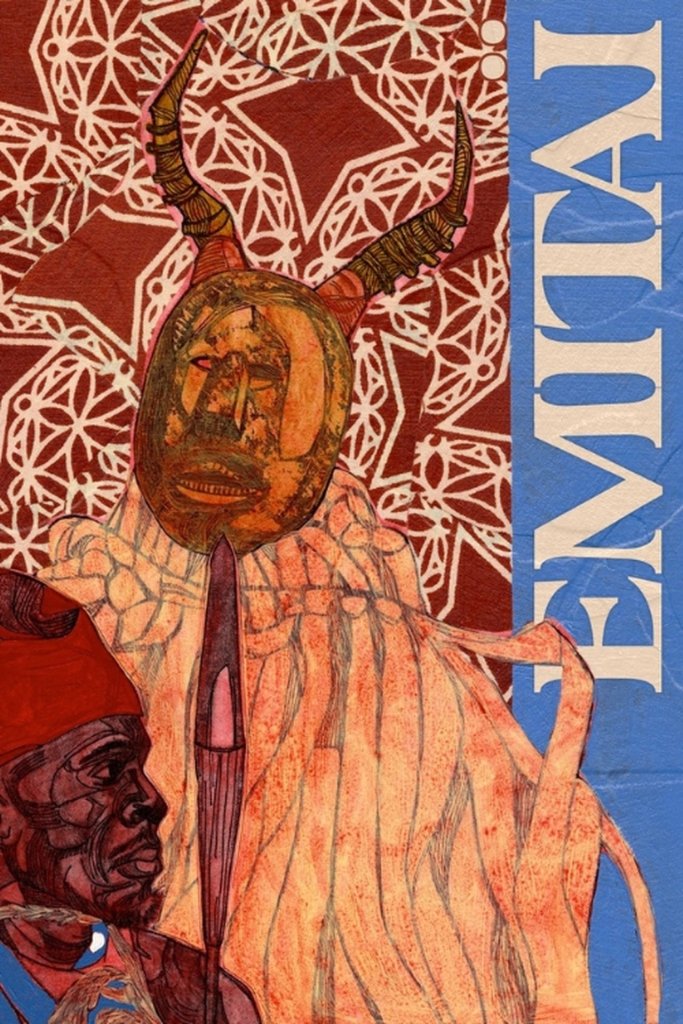

Emitaï is more about an event covering a specific time in Senegal’s history, more than a traditional story with a plot (or even main actors). During World War II, local men in tiny villages in Senegal are conscripted by the French army to go fight against the Germans, or as the villagers call it, the “white man’s war.” The men obviously don’t want to go, so a contingent of French soldiers (made up of all-ready drafted men from other villages in the area, led by a French white man) are brought in to force the enlistments. The film follows one long day during a standoff between the French army soldiers and one local village. First, men are rounded up and put into service, and then, when the army demands rice as a contribution to the war effort, the women hide the rice. To force compliance, the soldiers round up all the women and stick them in the middle of the village, exposed to the hot sun all day long. The elder men and tribe leaders, men who were too old to be drafted, consult their gods for ways out. They initially try to fight back, but the soldiers set up just outside of spear range and can easily shoot back with impunity, killing one leader. And since only women can perform the burial rites, and they are all stuck in the village, there’s a clash of cultures as to what happens next. I learned a lot from the movie, but as a piece of art it was more informative than enjoyable, with nonprofessional actors and a shoestring budget that distracted from the overall story. It’s also pretty dark (obviously), such as one French soldier who is from the area and knows all the village’s customs, using that knowledge to help his bosses rather than alleviate the plight of the villagers. And some misplaced humor doesn’t do enough to lighten the mood (when the French tear down posters extolling Marshall Petain and replace them when new ones of Charles de Gaulle, and act as if nothing has changed; for the villagers, nothing has). ★★

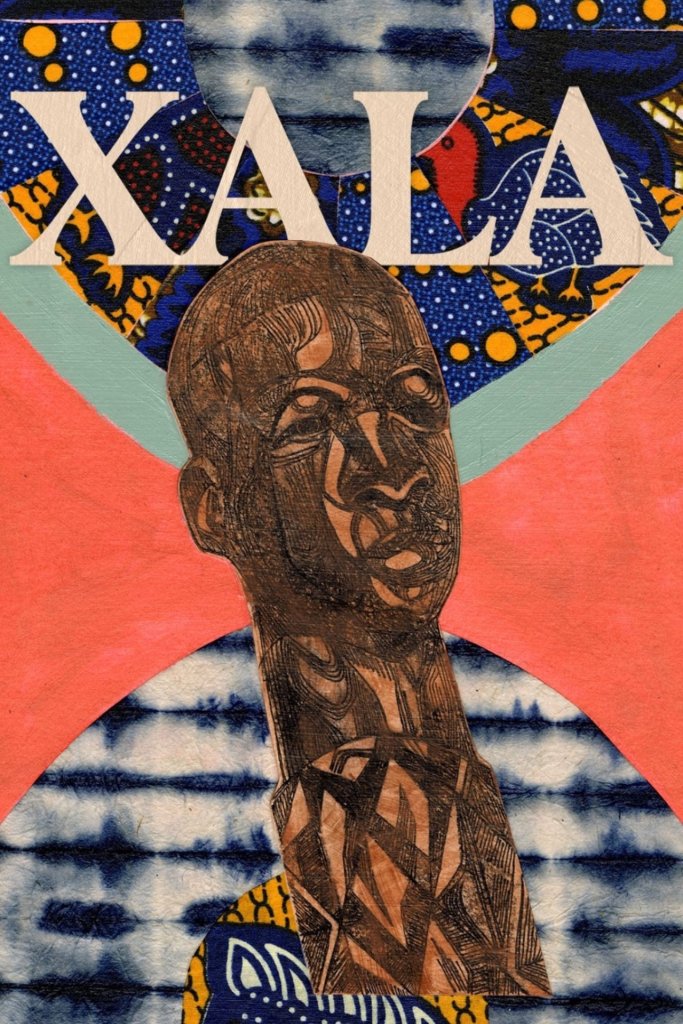

Xala is a comedy (I guess? Though a heavily political satire one) about the changing of the guard in Senegal after the end of French colonial rule. In the beginning of the film, there’s a big ceremony as white men are ushered out of the Chamber of Commerce and a new board of black men are given offices (though there’s a funny scene as the white men return with suitcases full of cash, and are given desks in the building again, obviously implying who is still running things). The rest of the film follows one man in the new financial system, El Hadji. El Hadji has two wives already and is currently set to marry a (much younger) third, when things start going sideways for him. On his wedding night, he is “unable to perform,” and suspects that someone has put a curse on him. He starts consulting local shamans, some of whom give good advice, some bad. While this is going on, his business ventures start having problems too, and he comes under investigation from the same Chamber where the film started. Though he points out that all of them are as corrupt as he, doesn’t seem like that will save him in the end. This movie, though quite funny at times, suffers from much the same problem as the above film. No real acting going on from the nonprofessionals, who are simply delivering lines, and often with long delays between the lines; it almost seems like (and probably was) they were being fed lines from offstage. Sometimes they even flub their lines, pause, and continue on, with no editing! It’s very distracting, to the point that it was, again, hard to enjoy, which is a shame because there are some truly funny moments in El Hadji’s tribulations. ★★½

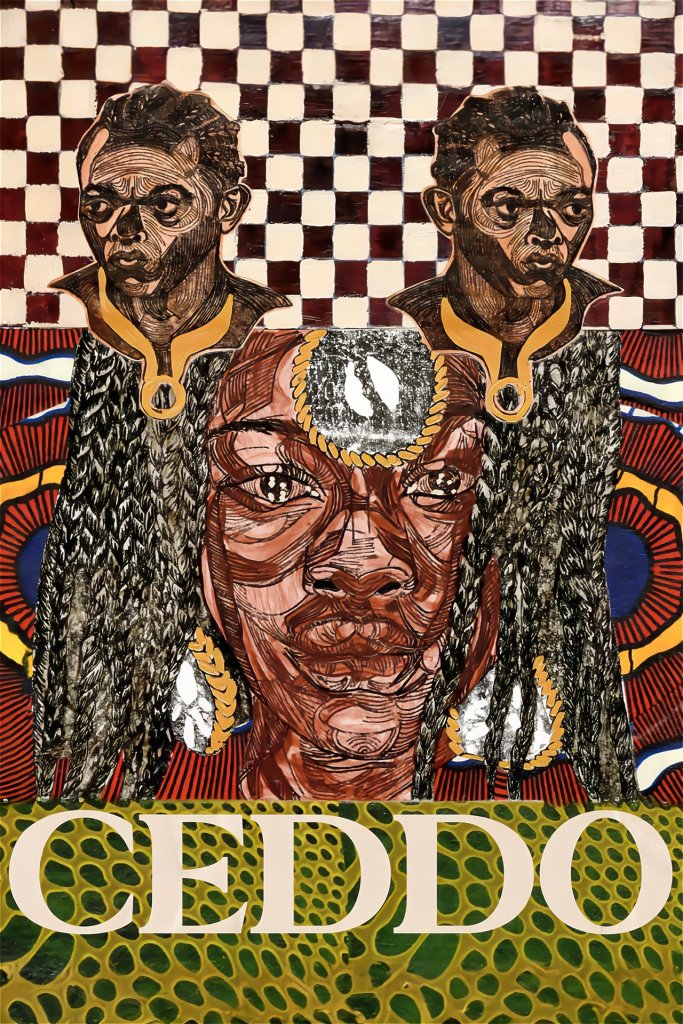

Ceddo is a historical film, looking at one village as it tries to protect its culture from invading forces. At the beginning of the movie, Islam and Christianity have already made their mark on the local population. The King and his immediate family have converted to Islam; this may have been due to self preservation, as when the influential imam gets a chance later in the film, he gives villagers the choice to convert or be sold into slavery. While the Muslims do hold sway politically, white Christian slavers are still very much in the picture as well. However, there is pushback from the general population too. Those who have not converted are called the Ceddo, or pagans, and they are trying to adhere to the old ways. One man, the King’s nephew, is by tradition supposed to marry the King’s daughter (his eldest child) and thus become next in line to the thrown, but the King has instead promised her to a warrior (who has converted to Islam), even has the King’s own son (second born) had hopes for the throne himself. To try to force the King’s hand, some Ceddo have kidnapped his daughter to try to force the King to stick to tradition. The two converted husband hopefuls (warrior and King’s son) attempt to rescue her, only to be killed by the Ceddo. The movie has some of the same problems as the two preceding films, but the story is very engaging, and presents a stark picture at a people’s resilience as they face the death of their way of life. ★★★

- TV series recently watched: Iron Fist (season 1), Ironheart (series)

- Book currently reading: Aftermath: Empire’s End by Chuck Wendig