I’ve got a quartet of films from French director Louis Malle, two in French and two in English, starting with The Lovers. This was his followup to his breakout Elevator to the Gallows (and in fact was released later that same year, in 1958), and has the same star, Jeanne Moreau. She plays Jeanne Tournier, a wealthy socialite living in a mansion in rural France, whose husband Henri runs a newspaper. Jeanne is bored with her life, and though her husband loves her, he works a lot and is always away. She has taken to going to Paris frequently to hang out with her friend Maggy, and has caught the eye of polo star Raoul. When Jeanne begins to suspect that her husband is having an affair, she gives herself permission to pursue Raoul too. Finally though, Henri, becoming suspicious himself, invites Maggy and Raoul out to their house for dinner one evening, much to Jeanne’s chagrin. To make matters worse, her car breaks down on the way home from Paris, ensuring that Maggy and Raoul will arrive before her. Jeanne is able to thumb a ride with middle class worker Bernard, who espouses on the drive all of the things that are wrong with the wealthy class and their inane way of life, and while Jeanne should feel attacked, she finds herself attracted to this young man who doesn’t have a care in the world. When they arrive to the mansion, Henri invites Bernard to stay for dinner too, setting up a much different ending than you may have expected. Wonderful story that flips the script on you, and a fine performance from the eye-catching Moreau who sucks you in to her outlook on life. ★★★½

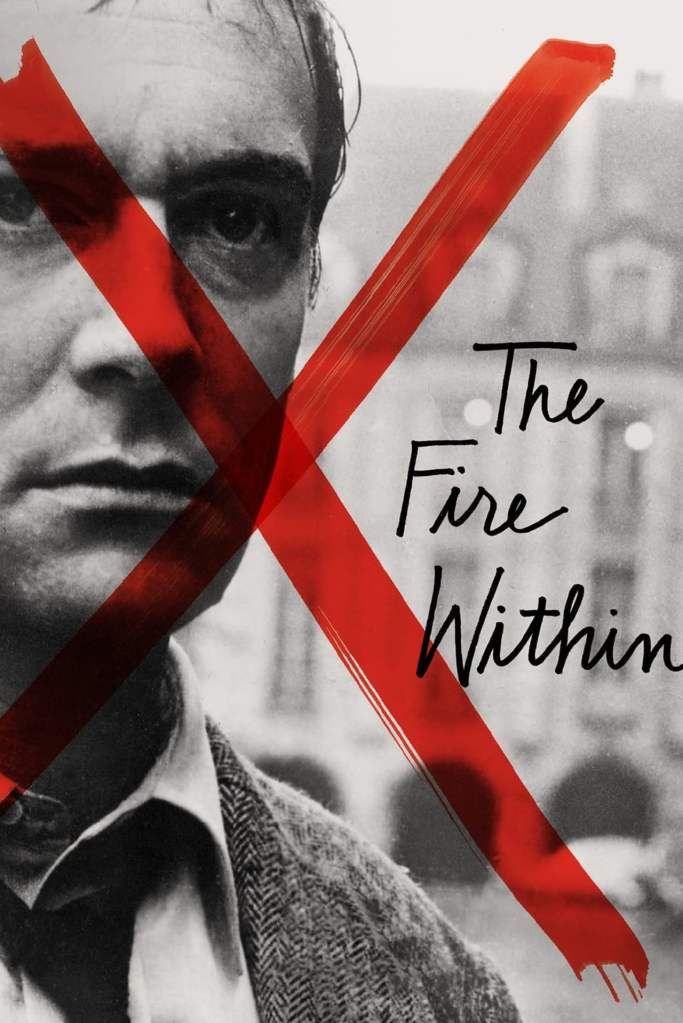

Funny enough, the other star from Gallows, Maurice Ronet, is in 1963’s The Fire Within, and plays a man named Alain. Alain is from France but was living with his American wife Dorothy in New York until 4 months ago, when he came back home to get sober at a health clinic in Versailles. The film opens with him waking up after an evening with another woman, family friend Lydia, who is about to go back to New York for work but who promises not to tell Dorothy of their tryst. Alain doesn’t seem to care much if Dorothy learns or not, as she hasn’t checked in on him while he’s been away, and he feels their life together is over. Alain begs Lydia to stay with him in France, but she refuses. If she knew how dire it was for Alain, she may have changed her mind, because he is ready to end his life, something he promises to himself he will do the next day. On that fateful day, we follow Alain as he revisits the bars he used to hang out in and the friends he had. They all remember the drunken Alain, and recall stories about when he was the life of the party, but he is a much different person now. He continually asks these old friends to stay with him, but they have each moved on to different things in life and are unable or unwilling to drop everything and help Alain out. It’s a dark and gloomy movie, and a pretty bleak outlook if are looking for hope in humanity, but damn if it isn’t still entirely engrossing until the very last scene. ★★★½

This is going to be a much longer review than my typical quick takes, as I have a lot to say about My Dinner With André. Written by its two stars (and really the only two actors in it, except for short lines by the staff at the restaurant) Wallace Shawn and André Gregory, the movie is almost entirely one evening at a fine restaurant in New York as two old friends catch up. The actors play fictionalized versions of themselves, and in fact was conceived as a way for real-life André to relate his experiences traveling the world. The premise is simple (and the movie itself deceptively simple too): Wallace is a playwright and sometimes actor in New York, who enjoys a simple life. If he has a cup of coffee and a newspaper waiting for him in the morning, then it will most likely be a good day. He recently ran into André, who was crying openly on the street after having just watched an Ingmar Bergman film, and quipped to Wallace, “I could always live in my art, but not in my life.” They agreed to meet for dinner, and that is where Wallace is heading at the beginning of the movie. In Wallace’s theater circles, there had been rumors of André’s eccentric life after having walked away from the business a few years prior. Wallace, who likes to keep to himself, is dreading the dinner, but reluctantly goes. He is in for a wild night, but more so are we the viewers. As Roger Ebert wrote in a review in 1991 upon revisiting the film (he was a huge fan too when it first came out, calling it the best film of 1981), the two characters “are simply carriers for a thrilling drama–a film with more action than “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” André has stories to tell, of Tibet, and the Sahara, and of being buried alive, and bringing a Japanese monk to live with him in New York with his family. Common threads are throughout though, which slowly come together as the evening progresses: we as a people have become numb, lost, and isolated from each other and from living life in general. To Wallace, who likes his isolation, this is as perplexing as an alien society, but André’s stories do move you to want to be better, to explore our world, and to remember to “smell the roses” and connect with our loved ones on a real, personal level. They even wax philosophical, with André believing in fate and the powers of the universe bringing things together, whereas Wallace only wants to believe in science. André tells his stories as a storyteller would hundreds of years ago; you could replace the dinner table with a campfire and have the same feeling of awe. A movie like this reminds me that you don’t need action scenes or love interests to grab your attention (in fact, they touch on that subject too, the current state of theater and entertainment). By the 30 minute mark of this 2 hour film I found myself leaning forward and hanging on every word, and am not ashamed to say I was moved to tears a couple times before the end too. Just from two guys talking. The movie also reminds me that I probably give 5 stars out far too often, as a film like this is miles above so much else that is out there. One that I could watch again and again. ★★★★★

By all accounts I should have enjoyed Vanya on 42nd Street, but I could not get into it at all and finally gave up about an hour in. I’m going to blame it on the source material, a late 19th century play, Uncle Vanya. The film came about after the actors, including André Gregory and Wallace Shawn from the above movie, as well as Larry Pine, Brooke Smith, and Julianne Moore, were getting together workshopping the play around New York. They’d meet in abandoned theaters, parks, or each other’s apartments, anywhere, just to read lines and get to understand better this famous play. Louis Malle attended one such get-together and proposed the idea to film it. The film begins with the actors meeting each other on the street in front of an old abandoned theater, and they come inside. With no warning, the play starts; it begins with a simple conversation and took me a couple minutes to realize they were now inside the play and not just actors talking to each other. I won’t recap the play because I didn’t stick around long enough to know how it all came together, but obviously the idea was to strip away the costumes and audience and props and just focus on the words, so it is all dialogue again. While the performances are fine, I could not get into the story and it all felt a bit too contrived. Unfortunately this was to be Malle’s last film, he would die a year later in 1995 from cancer. ★½