Been a hot minute since I saw some Japanese films, time to rectify that. I’ve been eyeing director Keisuke Kinoshita for awhile. A contemporary of some big names from Japan (Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi), he didn’t get a lot of credit outside of his home country. Some of his later films from the 50’s received some attention, and I’ll watch a couple of those too, but I wanted to see some of his earlier pieces too.

Port of Flowers was his first film, from 1943. In a small port town, a businessman a generation ago attempted to build a shipyard, but failed. The town revered him and his attempt to help their prosperity, and remember him long after he moved away. He recently died in Tokyo, and two grown men show up at the village claiming to be his sons, and they want to continue his legacy. Unfortunately for the town, the men are conning them; they want to sell shares for a fake shipbuilding company and then take off with the money. Things do not go as they planned though. Only expecting to get a couple thousand yen from the small town, they are instead moved by the generosity of the villagers, many of whom donate their life savings to the project. As well, one of the conmen falls for a pretty young lady in the village. Even when the two men try to cut their losses and head out, various circumstances keep them from leaving. The movie is slightly humorous, but unfortunately feels really drawn out, even at a crisp 82 minutes. The most fascinating part for me was its treatment of the outbreak of Japan’s involvement during World War II. I’ve seen many Japanese films made before the war, and many made just after (under the American occupation and film censors), but rarely one made during. The film depicts the locals’ reactions to the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the sinking of a British ship, and their excitement to going to war for the honor of their nation. ★★

The Living Magoroku also takes place in the early days of the war, again around a small village. There’s a lot of moving parts in the one, but it mostly centers around a man, Yoshihiro Onagi, whose family own the Onagi field. On that field 370 years ago, a great battle was fought, where Onagi’s ancestors kept at bay a much larger force, saving the town but ultimately costing them all their lives. Their sacrifice has made the field sacred. A generation ago, one of Onagi’s family members tried to cultivate the field, and a supposed curse was brought down, that all the men in the family would die young. So far it has held true, and Yoshihiro is the last of them. As such, he lives his life in fear. Into this setting comes the war. New soldiers want to cultivate the Onagi field to produce food for the war effort. As well, one of them wants to marry Yoshihiro’s sister, but Yoshihiro refuses for fear that the union will bring more men into the family who will die from the curse. Another soldier wishes to purchase Onagi’s samurai sword, made from a famous swordsmith hundreds of years ago and used in that fabled battle, but Yoshihiro refuses to part with the heirloom. Others characters include the local blacksmith, the Onagi’s generational servants, and others. Lots going on, but it all ends up tying into Yoshihiro and his fear of his fate. I liked it a bit more than the first; like many Japanese films from long ago there’s some aspects that are a bit over the top, but the story is well put together and everything works well in the end. ★★½

Kinoshita moves from the rural to the city in Jubilation Street, which takes place in the suburbs of Tokyo, and follows a handful of neighbors and friends who are being told they must leave their homes. Some of them have lived there for generations, but the government needs to expand the local factory for the war effort. In particular, one family stands out. Kiyo and her adult son Shingo have stayed in the area despite Shingo’s desire to leave; Kiyo has been waiting for her husband, Shingo’s father, to return. He left the family 10 years ago and never came back. Shingo is ready to move on, but Kiyo continues to hold out hope for him. The movie lays the propaganda on thick. Like the previous movie (and probably a lot of movies made during the war), there’s a huge sense of doing what is good for the country. By this time, Japan wasn’t faring too well in the war, and I’m sure the film companies were under pressure to drum up support in any way possible. Unfortunately that was to the detriment of this picture. ★½

Army is the first of these films that I really enjoyed, and it was the one that got the director in the most trouble. It is told over three generations of a family leading up to the present. Without getting into too many details, it details the men of the family and their various experiences in Japan’s many wars over the years. The newest young man in present day is Shintaro. His father was unable to serve in battle during the Sino-Japanese war, due to constant illness, so he has set all his hopes on Shintaro to redeem the family’s honor. Growing up in a strict and stern household, Shintaro initially isn’t a “manly man,” but by the end of the film, he does become a Private First Class, and is ready for battle in the current World War. I usually try to avoid spoilers, but the ending of this film is so excellent, and it is what got Kinoshita in hot water, so SPOILER: As Shintaro is marching off with his troop in a military parade before being shipped off, his mother sits at home reciting the military code of honor, trying to assuage her worry for her son. Wracked with concern, she runs to the parade and follows after Shintaro, tears flowing. Finally, she loses him in the crowd, and brings her hands together in a silent prayer. At a time when Japan was wanting to show that it was an honor to send your children to war (earlier in the film, the director put in the line, with supposed sincerity but which was obviously filled with sarcasm, “Those killed in the war died so we could have joy.”), this display of loss and fear over Shintaro’s fate was not acceptable. Kinoshita, later an admitted antimilitarist, was accused of treason, and was prohibited from making more films until after the war. ★★★★

Released in 1946 and no longer shackled by Japanese government/military sentiments, Kinoshita finally made a movie from his own heart. Morning for the Osone Family follows one family in the final years of the world war. Fujiko Osone is a single mother (her husband somewhat recently has died) with four older children. The father was a left-leaning, liberally minded man and his kids have mostly followed suite. In fact, the film opens with the arrest of the eldest son, Ichiro, a reporter, after he wrote a not-so-subtle antiwar piece in the paper. The middle child, Taiji, is an artist, but he doesn’t escape the war for long either, and is drafted. With a lack of men in the household, Fujiko’s brother-in-law, Issei, comes to live with them. Issei, a colonel in the army, is much more conservative and nationalist that his deceased brother was, and he urges the Osone family to not be so reluctant in their support of the war. He breaks off the engagement of the Osone daughter, Yuko, after Ichiro’s arrest and supposed black mark on the family’s honor, and then urges the youngest son, Takashi, to enlist in the army. Throughout it all, Fujiko acquiesces to Issei’s rules as the now “man of the house,” until at the end, when she can no longer bite her tongue. Kinoshita doesn’t hold back; he does his damndest to shoot holes at the right wing agenda he despised. A decent enough story, though heavy handed to the opposite extreme of his earlier films. ★★★

The five films above were this director’s first five movies; now I’m jumping ahead a bit to the two I most wanted to see, two of his more celebrated pictures. Twenty Four Eyes came out years later in 1954, and starts in the late 1920s. The eyes reference the eyes of a first grade class of 12 students, who have a new teacher. The new teacher, Hisako, causes a stir on her first day in the tiny farming and fishing village, arriving in “western clothes” (skirt and suit jacket) and riding a bike. Oh the shame! But the kids love her, and are dismayed when she hurts her leg and is no longer able to make the long commute to work. Hisako is transferred to the main school closer to her home, and promises the kids she’ll see them again when they get bigger and transfer there themselves; that’s where the film jumps ahead, 5 years later. As the kids have gotten older, their poor situations at home have come to the forefront. Hisako has to help kids through tough family situations, including watching some have to drop out of school to do needed housework or help raise siblings. Unfortunately some of her advice gets her in trouble with her bosses, who warn her to not come off as a communist. Frustrated that she cannot guide students as she would wish, and butting heads with the establishment which pushes militarism on the student body, Hisako resigns, and asks her students to keep in touch. From there the film jumps ahead another 8 years, to the early 1940s, and continues through the World War, and its consequences for Hisako and the group of kids she watched grow up. The movie is overly sentimental, perhaps too much at times, trying at every turn to elicit tears from the viewer. In the end, it becomes a sob fest for the actors. It can be cheesy, but is often endearingly cheesy. ★★★

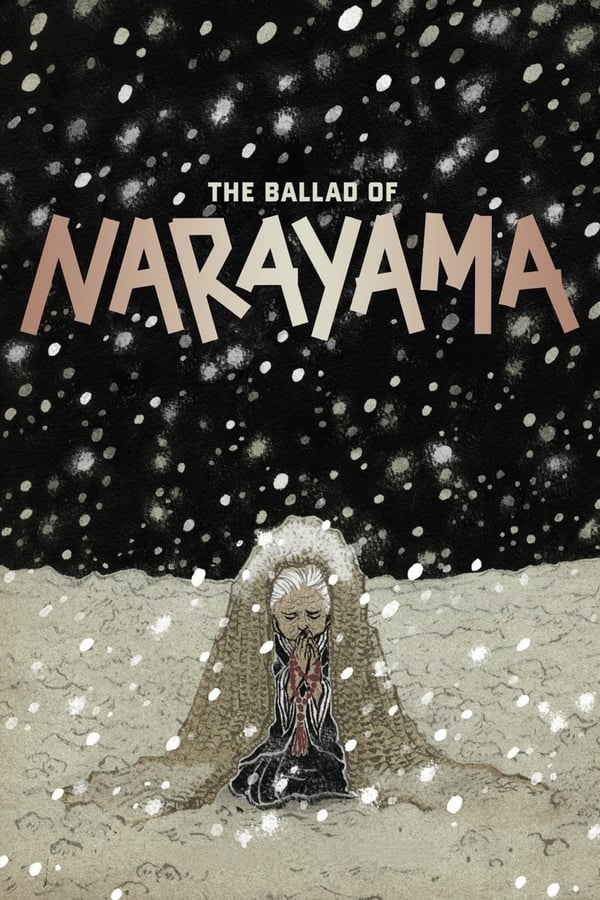

The Ballad of Narayama simply amazed me from its opening scenes. It is staged like a classic Kabuki drama (sans the over-the-top makeup), even going so far as to give the illusion of sets being rolled away between scenes. The story is light but extremely well developed. In a tiny village, the elderly are carried up the mountain of Narayama by their children once they hit the age of 70, and left up there to die. The center figure in the movie is Orin, a woman who’s lived a simple but good life. Whereas many people look towards their birthday with fear, and in fact, there’s a humorous subplot about a man who’s been fighting his kids over his own journey up Narayama for quite some time, Orin is looking forward to it, and the peace that comes with death after a long and happy life. Orin’s son is a thoughtful and kind man who loves his mother dearly, and would love to find a way out of this tradition if possible. Her grandson though is a little brat who doesn’t know how much he’ll miss Orin’s cooking until she’s gone. Superbly done, with richly detailed sets that completely immerse the viewer with vibrant colors in a glorious wide screen, this movie captivated me like few do these days. It’s a powerful, sometimes haunting film, with lasting imagery that you won’t quickly forget. ★★★★★

- TV series currently watching: none

- Book currently reading: Dune Messiah by Frank Herbert

One thought on “Quick takes on The Ballad of Narayama and other Kinoshita films”