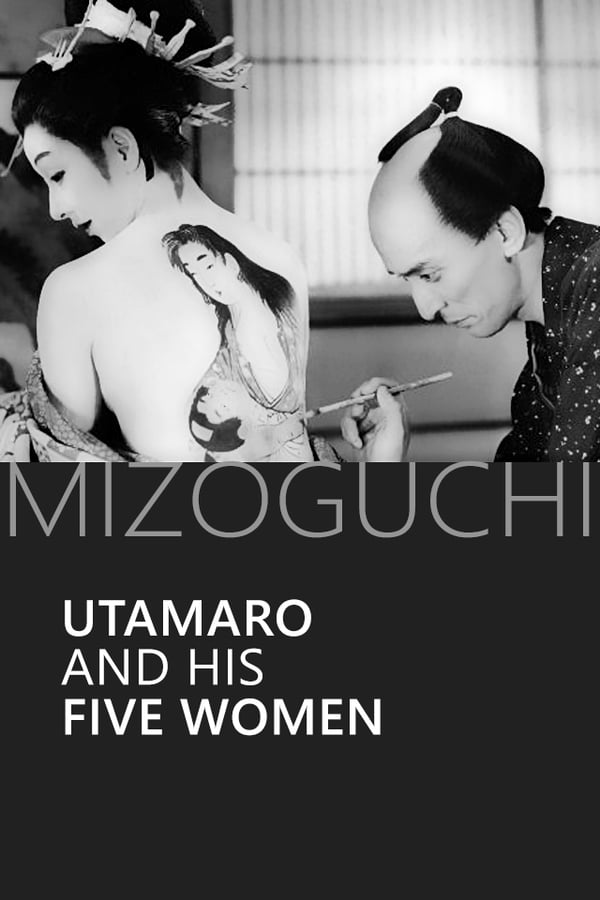

Going to look at some of the films from acclaimed Japanese director Kenji Mizoguchi, starting with 1946’s Utamaro and His Five Women. Released during the USA occupation of Japan after World War II, it is a rare historical film during this era, when the US censors were not allowing many Jidaigeki (Japanese period films) to be made, considering them too nationalistic. The title is misleading, because while the story does revolve around Kitagawa Utamaro, a famous Japanese painter of the late 18th century, there are a whole lot of main characters. The film focuses on several relationships floating around Utamaro’s sphere. Koide is from a well-to-do family but leaves that life behind to study with Utamaro. His betrothed, Yukie, also leaves her upper class family to follow him later, but he’s already turned his attentions to a local courtesan. Shozaburo is a tattoo artist who traces one of Utamaro’s drawings onto the back of a beautiful courtesan named Orui, and then falls in love with her and elopes, leaving his own fiancee Okita behind. Utamaro himself falls in love with a commoner named Oran, but gets into trouble with the law for some of his practices. There’s a whole lot going on here, and honestly I was a bit lost for awhile. There’s a lot of characters, and the fact that many of the girls’ names start with “O” didn’t help; guess I should have paid more attention early on. The copy I watched was not a great restoration, so that didn’t help either. Still, it’s a decent enough picture, from a turbulent time in Japan’s history. ★★½

The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum is a beautiful picture about an actor striving to perfect his craft. Adopted by the famous actor Kikugoro, Kikunosuke is his protege and heir, but he can’t seem to find his muse. Kiku is flattered by fans and false admirers who only want to curry favor from his father, but he is spoken to plainly by his younger brother’s wet nurse, Otoku. Kiku ends up falling in love with her, but his father forbids the match to a girl beneath their station, and disavows Kiku. Kiku flees to a new city and begins studying under a different famous actor, taking the name Shoku to differentiate himself, but a year later, his skills have gotten no better and he’s getting booed off the stage. Otoku tracks him down just as he’s about to quit for good, and convinces him to not give up on his dreams. Things don’t turn around though: Kiku’s new master dies, leaving him to take the only available job with a traveling theater troupe, a lowly position for a trained actor like himself. That too falls apart after just a couple years, and Kiku and Otoku are penniless and living in public housing. Unbeknownst to Kiku, Otoku goes to Kiku’s brother, Kikugoro’s son, and begs for one more chance for Kiku. Kiku is given a starring role, on the condition that Otoku leaves him, but will he finally see his dreams come true, only to lose his love? It’s a lovely, sometimes heartbreaking film. Dating to 1939 Japan, the video quality is definitely rough around the edges, but worthy of a viewing. Mizoguchi’s camera work is a sight to see. He uses a lot of long takes, including many long tracking shots as characters walk around, that I’m sure wasn’t easy to pull off in its era. ★★★

Mizoguchi was popular in Japan long before 1952’s The Life of Oharu, but it was this tragic tale that put him on the international stage. In the beginning, a 50-year-old Oharu is a prostitute who has been unable to find work this night, due to her aging looks. Her fellow women of the night gossip how she used to live in the palace, and ask what brought her so low, so we get a flashback. Raised as the daughter of a samurai, Oharu had a life of luxury, but fell in love with a lowly retainer. When their relationship was found out, the man was executed and Oharu and her family banished from Kyoto. A couple years later, a powerful lord is looking for a concubine to deliver him an heir, as his wife has been unable to get pregnant. He is very choosy about looks and features, so a host of women are dismissed until they find Oharu. Initially she doesn’t want to go along with it, but ultimately she has no say in the matter. She is moved back to Kyoto and does indeed give the lord a son. Her father is anticipating riches to start coming in, since he is the blood father to the heir of the lordship, and has wracked up some debt, but Oharu is no longer needed at court, and is dismissed. Her father sells Oharu off to pay his debt, first as a high end courtesan, but that is but the next step in her life of misfortunes. All that takes place in just the first hour of this 2 hour film. Oharu’s life is full of heartache and tragedy, with only all-too-brief moments of happiness. By the end, her hard life has taken her looks, and we just hope that she can find some resolution before it’s over. It’s a poignant film, about a woman with very little power over her own life. ★★★★

There’s some good films listed above, but Sansho the Bailiff is the best yet, a true masterpiece, right up there with Ugetsu. Based on centuries-old folklore passed down from storyteller to storyteller, it’s a movie without a lot of happy moments, in fact, there may only be one. It opens with a governor being exiled by the higher-ups, for something he did to help the poor living in his district. He is sent far away, and a few years later, his wife and two children, Zushio and Anju, are traveling to him. They are told of a shortcut over water by a woman, but the next morning, they find that they’ve been tricked. The mother is separated from her children and sold off as a prostitute, while the kids are sold as slaves to a local bailiff, the terrible Sansho. Sansho holds government favor for running a tight ship on his land, which he does through cruel treatment of his slaves and zero tolerance for poor discipline. Zushio and Anju are given new names by a friendly slave, who knows that if their true identities as a former governor’s children is know, they’d be targeted. 10 years later, they are still toiling on Sansho’s land, and while Anju still dreams of escaping one day to find their parents, Zushio has become a trusted and cruel leader under Sansho’s regime. When a new slave sings a song heard sung by a courtesan in far away Sado, about seeking her lost children Zushio and Anju, Anju knows that her mother still lives, and finally convinces Zushio it is time to make their escape. Zushio makes it out, but Anju does not. Zushio finds a powerful friend to help raise his station, and he attempts to follow in his father’s footsteps in freeing those laboring under Sansho. The ending is bittersweet, but this isn’t meant to be a feel-good film. This is one of those transcending pictures about the course of humanity, and what makes us worthy as human beings, especially in regards to the treatment of others. Don’t expect any warm fuzzies, but do expect to be moved. ★★★★★

A Story from Chikamatsu (also called The Crucified Lovers) follows a duo destined to be intertwined. In feudal Japan, Mohei works at a successful scroll-making shop, run by a Scrooge-like man named Ishun. Ishun puts on a front that he’s better than everyone else, and his large government contracts feed that ego, but he’s hiding the fact that he’s a womanizer. His much younger wife Osan married Ishun for his wealth, which has already saved her family from destitution, but she needs more money. However, Ishun is no longer giving out loans to anyone, not even the in-laws. On the side, he’s been stealing into another young worker’s bedroom at night, Otama. When Osan hears of her husbands infidelities, she sets a trap by pretending to sleep in Otama’s room. However, it is Mohei who comes to her room that night, thinking he is going to say goodbye to Otama before he leaves. He and Osan are caught together in an innocent embrace, and the rumor is started that they are sleeping together. To avoid the strict laws of death to adulterers, Mohei and Osan flee. While on the lamb, they do begin to have feelings for each other, so by the time they are caught, their situation has gotten very complicated. There’s some beautiful scenes in this film, and some quiet and contemplative moments that tug at the heart, but the plot is simple and the dialogue drips of sappiness too often. Enough good moments to offset some of the ham, but just barely. ★★½

One thought on “Quick takes on 5 Mizoguchi films”